- Home

- Sharon Bolton

Like This, for Ever Page 6

Like This, for Ever Read online

Page 6

As Barney walked along the hall towards the kitchen, he heard the sounds of Daybreak on the kitchen TV and something else that was wrong.

The washing machine was on. They never did washing on Friday. Saturday was washing day. They did four loads every Saturday. A whites wash, a coloureds wash, bed linen and then towels. The washing was Barney’s job, because he quite liked the sorting into organized piles, and the idea of putting dirty stuff in and getting clean, sweet-smelling, damp clothes out. His dad did the ironing.

‘What’s going on?’ he said, as he walked into the kitchen, his eyes going straight to the washing machine. Yep, there it was, something pale and stripy sloshing about.

‘Breakfast’s ready,’ said his dad, who was sitting at the central island, a cereal spoon in his right hand. Barney didn’t move. His dad had used too much soap. There was too much froth in the machine.

‘I spilt a mug of tea in bed this morning,’ said his dad. ‘I didn’t want it staining. That’s OK, isn’t it? For once?’

‘’Course,’ said Barney, making himself look away from the washing machine. So did that mean they’d only do three loads the next day? Odd numbers had a way of making him feel twitchy inside.

‘Barney!’ His dad was reaching out across the island towards him, putting his own large hands over Barney’s small ones. ‘You’re doing it again.’

Barney shrugged and concentrated on making his hands relax. He couldn’t remember it, but he knew they’d been tracing patterns on the granite surface, his fingers moving in repetitive squared shapes, over and over, even when his hands started to hurt, either until someone stopped him or he was distracted by something else.

‘Raisins,’ said his dad.

The raisins were by his right hand. The bran flakes had already been poured into the bowl. Barney counted four raisins into his bowl as the 8am news came on, his dad adjusted the volume and a tall man in a suit told the world what most of it already knew – that the bodies of Jason and Joshua Barlow had been found the previous evening and that the police believed they’d been killed by the same person who’d previously abducted and murdered Ryan Jackson and Noah Moore. He reminded them that a fifth boy, Tyler King, was still missing.

The tall man, a senior police officer of some kind, was sitting behind a table with three other people. As the next four raisins landed on the bran flakes, the cameras moved along the table to the parents. The bones of the father’s skull seemed to be pressing themselves out through his skin as he asked the viewers to help find their sons’ killer. The mother didn’t manage to articulate a single word. She was crying too much.

At least Jason and Joshua had had a mother.

As the last four of his sixteen raisins went into his cereal bowl, a dark-skinned, dark-haired woman appeared on the screen. The name card on the desk in front of her said that she was Detective Inspector Dana Tulloch.

‘Someone knows who this killer is,’ she was saying. ‘This killer doesn’t appear from nowhere and then vanish again. He lives among us. If you have any information that you think could be helpful, however small, however unimportant it may seem, please get in touch.’

The news moved on to the next story and Barney’s dad turned the volume down again.

‘Toast?’ he said, getting up.

‘Please,’ said Barney. ‘Can I have maple syrup and honey?’

‘No, because that would be disgusting.’

‘I mean honey on one half and maple syrup on the other.’

With a heavy sigh and a resigned shake of the head, his dad reached up into the cupboard. ‘Barney, I’m not sure I want you going out in the mornings at the moment.’

Instant panic. Barney looked from the TV over towards his dad. ‘Why not?’

His dad turned to face him. ‘It’s too dark,’ he said. ‘Maybe when it gets lighter, in the summer.’

‘If I give my job up now, I won’t get it back again just because the working conditions become better,’ said Barney.

His dad almost smiled and then caught the look on Barney’s face.

‘I just don’t feel comfortable about you being out on your own right now.’

But he felt perfectly comfortable leaving him on his own two nights every week. OK, that was hardly fair. Barney was the one who refused ever to have babysitters in the house, who’d kicked up a massive fuss on the few occasions, now years ago, when his dad had arranged one. Babysitters just never understood how things needed to be done. Babysitters moved things. Babysitters came into his room when he was working and asked nosy questions. Babysitters … yeah, his dad had finally got the message, and for years Barney’s dad just hadn’t gone out at all. Only in the last few months had he started to trust Barney on his own.

‘Don’t glare at me, Barney.’

‘I’m not,’ Barney said, although he knew he had been. Then the toast popped up and his dad began the process of buttering and spreading. While his dad’s attention was elsewhere, Barney reached for the remote control, turned down the volume and switched the channel.

‘You wouldn’t answer the door, would you?’ his dad said, as he handed him the toast. ‘If anyone knocked when I’m not here. You’d phone me.’

‘’Course,’ said Barney through a mouthful. On the TV, three men in swimming trunks, yellow beanie hats and goggles were getting into three bath-tubs. One had been filled with chicken curry, the second with soy sauce and the third, blackcurrant juice. It was an experiment to find Britain’s stainiest food.

‘Are you sure you don’t want me to organize someone to keep you company? We can find someone you like. Maybe an older boy? Jorge, perhaps?’

The men on the TV screen were sponging themselves down. Just gross!

‘Barney!’

‘What?’

‘Can we think again about a babysitter?’ said his dad in a voice that made it clear it wasn’t for the first time. ‘For Tuesdays and Thursdays, when I have to work late.’

13

‘MIKE, PLEASE.’

The pathologist, Dr Michael Kaytes, turned round in surprise. He’d been about to switch on the iPlayer in the corner of the mortuary examination room. Whilst cutting open bodies and removing internal organs, Kaytes liked to listen to Beethoven. Dana was convinced he did it for effect. Usually it didn’t bother her. Usually.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Dana, knowing she looked anything but apologetic, and not caring. ‘I’m just not sure I can cope with the music. Not this time.’

Kaytes nodded slowly. ‘As you wish.’ He walked back to the two gurneys in the centre of the room where Jason and Joshua Barlow’s bodies lay under blue plastic. Dana knew Stenning and Anderson were exchanging uncomfortable glances behind her back. Well, it was just tough. These were ten-year-old boys they were dealing with and if anyone could be blasé about that, she wasn’t sure she wanted them on her team.

Jesus, she had to calm down.

She watched, teeth clenched, as Kaytes and his young technician, Troy, peeled back the sheets. Kaytes was a tall man, barrel-chested and with a thatch of thick grey hair. His eyes were bright blue. Beside him, thin, small, colourless Troy looked like an undernourished teenager.

The gurneys had been labelled, to make it obvious which twin was which. Those little faces would have been so cute, so cheeky in life.

‘We got straight on to it,’ said Kaytes. ‘I thought you’d want the facts as soon as possible.’

‘Thank you,’ said Dana. ‘Is it the same killer?’

Kaytes nodded. ‘Almost certainly,’ he said. ‘Same cause of death: extensive bleeding following the severance of the carotid artery. Neither boy was sexually abused, no evidence of prolonged physical brutality of any sort.’

‘Are you sure?’ asked Anderson.

Kaytes nodded. ‘Hair missing around the wrists and ankles, consistent with strong packaging tape being wrapped around them,’ he went on. ‘Some bruises that would indicate struggling, the most recent of these along the left side of Joshua’s body.’

Dana nodded. Yesterday, Joshua had been a prisoner for almost two days. He’d have been scared, but the will to live, to escape if possible, would have been strong.

‘Like our previous two victims,’ continued Kaytes, ‘these both have a scattering of wooden splinters on the back of their shoulders and upper arms, consistent with their being held immobile on some sort of wooden bench or trestle table.’

These children had been strapped down for two days. They’d squirmed and wriggled to get free, and at some point Joshua had probably tipped the table over and landed heavily on his left side.

‘Their last meal was crisps and some sort of chocolate candy bar,’ said Kaytes. ‘They ate about two hours before they died. Again similar to the stomach contents of the previous two victims. Whoever’s holding them, he’s not big on healthy eating.’

A woman would make them eat properly, wouldn’t she? Dana felt her conviction wavering. On the other hand, would you worry about vitamins if you knew you were going to cut the kid’s throat days down the line?

‘Same murder weapon?’ asked Anderson.

‘Like the previous two victims, these two chaps were killed by a straight-edged, sharp blade, seven to ten inches long. Difficult to say, beyond that. But I am glad you brought that up. Because in one respect, Jason at least does differ from the previous two. Come and look.’

He stepped closer, extended a gloved hand and laid it on Jason’s forehead. As he tilted the boy’s head back, Troy shone a lamp directly at the wound on the throat.

‘We’re going to get this photographed and blown up to make it clearer, but for now, can you see?’ Kaytes ran his gloved index finger close to the edge of the wound. A millimetre or so beneath the cut was a thin, pink line.

‘Is that another cut?’ asked Dana.

Kaytes nodded. ‘That’s exactly what it is,’ he said. ‘And whilst it’s very indistinct, we’re pretty certain there’s a third cut here as well.’

‘Hesitation wounds?’ asked Dana.

Kaytes shook his head. ‘No. The previous two were made earlier – sorry to sound a bit Blue Peter. They had chance to start healing.’

Dana straightened up, looked at Anderson and then Stenning.

‘What the hell’s he doing? Practising?’ said Anderson.

‘To be absolutely honest with you, we saw something on Ryan’s corpse that made us wonder,’ said Kaytes. ‘It just wasn’t clear enough to draw any conclusions from. But what seems to be happening is that your perpetrator starts making cuts on his victims’ throats some time before he kills them. They’ll be much smaller cuts, of course, or else they’d bleed out. He cuts them, and lets them heal.’

‘And then he cuts them again,’ said Dana.

Silence for a moment, as each person in the room seemed to be mulling over what that could possibly mean.

‘Anything else, Mike?’ asked Dana after a while. She watched the pathologist glance at his assistant then nod his head fractionally.

‘I’ll let Troy tell you,’ he said.

The younger man’s vowels were straight out of Southend. ‘I noticed some bruising I thought was interesting,’ he said. ‘I spotted it on Joshua, but there’s some marks on Jason too, although fainter. Come a bit closer.’

Troy put his fingers gently beneath Joshua’s chin. Fractionally, he tipped the child’s head back and his boss increased the amount of light shining on the boy’s face.

‘Faint bruising, can you see?’ said Troy. ‘On the neck, under the jawbone, both sides of the head.’

Anderson and Stenning were nodding thoughtfully.

‘Same thing on Jason?’ asked Stenning.

‘There is, but fainter.’

‘Were they made when the boys were killed?’ asked Dana. ‘They look like restraint marks to me.’

‘They look exactly like restraint marks, but they’re older than the wounds. I’d say these marks were made on the day the boys were taken, not the day they died,’ said Troy. ‘It’s also my view, and Dr Kaytes doesn’t disagree, that these marks are on the exact site of the carotid baroreceptor.’

‘Troy studies martial arts,’ said Kaytes. ‘I’d have written them off as restraint marks; he thinks they could be more significant.’

‘Nothing on the others?’ Dana asked, speaking directly to Troy now. ‘The earlier victims?’

‘Not in this exact spot, but to be honest, these are very faint bruises. I’d expect them to disappear after a day or two,’ Troy told her.

‘So Ryan and Noah could have had them, but there was chance for them to fade?’ said Anderson.

‘Exactly,’ said Troy.

‘Could explain a lot,’ said Anderson. At his side, Stenning was nodding in agreement.

14

‘COULD YOU TELL me what they did to you?’ asked the counsellor.

‘I assumed you’d read the files,’ replied Lacey. ‘That you’d already know.’

‘I’ve read all the files on the Cambridge operation. But this isn’t about what I know or don’t know, it’s about whether you’re strong enough to talk about it yet.’

The small room in Guy’s Hospital was windowless and Lacey could never quite remember whether she’d pressed the lift to go up to one of over thirty floors, or down into the basement. She could be underground, she could be fifteen storeys up. Once in the room, there was no way of knowing.

And the corridor outside was always so silent; as though no one but she ever walked it, no one but she ever came to this small, square, dimly lit room, in which sharp edges probably existed but faded to ambiguous shadings in the gloom. There was a couch, two semi-comfortable chairs and a desk. A reading lamp was the only source of light. Lacey sometimes wondered if the woman she came to see twice a week was nocturnal, unable to face sunlight, even bright artificial light. Perhaps she was doomed to lead a sub-terranean existence, dependent upon the needy and the disturbed for her interaction with the outside world.

Lacey watched the second hand glide round the face of the wall clock. Two pounds a minute, this woman’s time was worth. Every thirty seconds, ching, another pound gone. It was worse than being in a black cab stuck in traffic. Thank God she wasn’t paying the bill herself.

And once again, she was expected to talk about the time, not much more than a month ago, when she’d come up against a new kind of evil. A depravity in which victims were stalked relentlessly, tortured with their own worst fears, before being thrown headlong into a downward spiral that ended only in self-destruction. She’d come so close to being one of those victims and now this woman, who knew nothing about real evil, was interpreting her reluctance to share details as weakness.

‘I’ll have to say it all in court,’ Lacey said at last. ‘I’ll have to spell out every last detail in front of a hundred strangers. I think that will probably do me.’

She could never bring herself to lie on the couch. Having to talk about herself made her feel vulnerable enough; doing it prone would be a step too far. So she sat, in the chair directly facing the counsellor. Sometimes she and the counsellor held eye contact for long seconds without speaking.

‘Well, that won’t be easy,’ the counsellor said, after the better part of a minute. ‘It might help to go through it with me first.’

‘I had to make statements from my hospital bed,’ said Lacey. ‘Then, when I got out, I had to go through it all again, just in case there was any question of statements made in hospital somehow being inadmissible. I’ve done it twice already, I think a third time should pay for all, don’t you?’

The woman glanced down at her notes, as th

ough to check which of her pre-prepared questions she’d reached. ‘Are you ashamed of what happened?’ she asked.

The counsellor’s eyes were grey, like her hair and her clothes. She was a grey lady, but her skin was too pink to belong to a ghost. ‘I’m not sure I understand,’ said Lacey, although she understood perfectly.

‘Do you feel embarrassed? Weak? As though your colleagues are judging you?’

‘Are they judging me? Is that in the file too?’

It was a game they played, twice each week. The counsellor asked questions and Lacey dealt with them, just occasionally, when she judged the moment was right, giving a little bit more away. She’d played the game before, years earlier, trying to convince police counsellors she was fit to be a police officer. Strange that it should be so much harder, convincing them that she wasn’t.

‘You were sent in to investigate, you became one of the victims. Some people might consider they’d failed.’

The woman was trying to get a rise out of her. Did she really imagine it would be that easy?

‘I’m still alive. Most of the other girls aren’t. I’d say that makes me a survivor, wouldn’t you?’

The counsellor pulled one of her rare smiles out of the ration-book. She wasn’t unfriendly, Lacey had decided at one of their earlier sessions, just one of those people who didn’t smile easily.

‘Yes,’ she agreed. ‘I would. And you caught the people responsible. From what I understand, they’re all going to prison for a very long time. Not that you can always prejudge these things, of course.’

Time to give a little. Lacey gave a deep sigh, dropped her eyes to the carpet. ‘I never think about it,’ she said in a low voice. ‘About what they did to me that last night. If I catch myself on the verge I have to push it right away, because if I let all those thoughts in, I think my head might explode.’

The other woman was leaning forward in her seat, the way she always did when she felt she was getting somewhere. ‘Go on, Lacey,’ she said.

The Split

The Split Daisy in Chains

Daisy in Chains The Craftsman

The Craftsman A Dark and Twisted Tide

A Dark and Twisted Tide Little Black Lies

Little Black Lies Here Be Dragons: A Short Story

Here Be Dragons: A Short Story Alive

Alive Like This, for Ever

Like This, for Ever Now You See Me

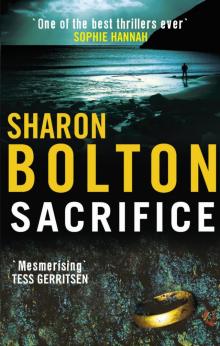

Now You See Me Sacrifice

Sacrifice