- Home

- Sharon Bolton

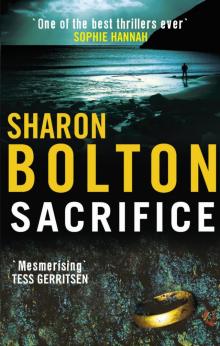

Sacrifice

Sacrifice Read online

About the Book

Moving to remote Shetland has been unsettling enough for consultant surgeon Tora Hamilton, even before the gruesome discovery she makes one rain-drenched afternoon . . .

The corpse I could cope with. It was the context that threw me . . .

Deep in the peat soil of her field she uncovers the body of a young woman. Her heart has been removed, and the marks etched into the woman’s skin bear an eerie resemblance to carvings Tora has seen in her own cellar.

And there I’d been, thinking the day couldn’t possibly get any worse.

But as Tora begins to ask questions, terrifying threats start rolling in like the cold island mists . . .

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Author’s Note

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Epilogue

Afterword

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Sharon Bolton

Copyright

Sacrifice

Sharon Bolton

For Andrew, who makes everything possible;

and for Hal, who makes it worthwhile.

Author’s Note

Sacrifice is a work of the imagination, inspired by Shetland legend. Whilst I used common Shetland surnames for authenticity, none of the Shetland characters in my book is based on any real person, living or dead. The Franklin Stone Hospital is not intended to be the Gilbert Bain, and Tronal island, as I have described it, does not exist.

I have no reason to believe that any of the events in my book have ever taken place on Shetland.

‘There are nights when the wolves are silent and only the moon howls.’

George Carlin

1

THE CORPSE I could cope with. It was the context that threw me.

We who make our living from the frailties of the human body accept, almost as part of our terms and conditions, an ever-increasing familiarity with death. For most people, an element of mystery shrouds the departure of the soul from its earthly home of bone, muscle, fat and sinew. For us, the business of death and decay is gradually but relentlessly stripped bare, beginning with the introductory anatomy lesson and our first glimpse of human forms draped under white sheets in a room gleaming with clinical steel.

Over the years, I had seen death, dissected death, smelled death, prodded, weighed and probed death, sometimes even heard death (the soft, whispery sounds a corpse can make as fluids settle) more times than I could count. And I’d become perfectly accustomed to death. I just never expected it to jump out and yell ‘Boo!’

Someone asked me once, during a pub-lunch debate on the merits of various detective dramas, how I’d react if I came across a real live body. I’d known exactly what he meant and he’d smiled even as the daft words left his mouth. I’d told him I didn’t know. But I’d thought about it from time to time. What would I do if Joe Cadaver were to catch me by surprise? Would professional detachment click in, prompting me to check for vitals, make mental notes of condition and surroundings; or would I scream and run?

And then came the day I found out.

It was just starting to rain as I climbed into the mini-excavator I’d hired that morning. The drops were gentle, almost pleasant, but a dark cloud overhead told me not to expect a light spring shower. We might be in early May but, this far north, heavy rain was still an almost daily occurrence. It struck me that digging in wet conditions might be dangerous, but I started the engine even so.

Jamie lay on his side about twenty yards up the hill. Two legs, the right hind and fore, lay along the ground. The left pair stuck out away from his body, each hoof hovering a foot above the turf. Had he been asleep, his pose would have been comic; dead, it was grotesque. Swarms of flies were buzzing around his head and his anus. Decomposition begins at the moment of death and I knew it was already mustering speed inside Jamie. Unseen bacteria would be eating away at his internal organs. Flies would have laid their eggs and within hours the maggots would hatch and start tearing their way through his flesh. To cap it all, a hooded crow perched on the fence near by, his gaze shifting from Jamie to me.

Goddamned bird wants his eyes, I thought, his beautiful, tender brown eyes. I wasn’t sure I was up to burying Jamie by myself, but I couldn’t just sit by and watch while crows and maggots turned my best friend into a takeaway.

I put my right hand on the throttle and pulled it back to increase the revs. I felt the hydraulics kick in and pushed both steering sticks. The digger lurched forwards and started to climb.

Reaching the steeper part of the hill, I calculated quickly. I would need a big hole, at least six, maybe eight feet deep. Jamie was a fair-sized horse, fifteen hands and long in the back. I would have to dig an eight-foot cube on sloping ground. That was a lot of earth, the conditions were far from ideal and I was no digger driver; a twenty-minute lesson in the plant-hire yard and I was on my own. I expected Duncan home in twenty-four hours and I wondered if it might, after all, be better to wait. On the fencepost the crow smirked and did a cocky little side-step shuffle. I clenched my teeth and pushed the controls forward again.

In the paddock to my right, Charles and Henry watched me, their handsome, sad faces drooping over the fence. Some people will tell you that horses are stupid creatures. Never believe it! These noble animals have souls and those two were sharing my pain as the digger and I rolled our way up towards Jamie.

Two yards away I stopped and jumped down.

Some of the flies had the decency to withdraw to a respectful distance as I knelt down beside Jamie and stroked his black mane. Ten years ago, when he’d been a young horse and I was a house officer at St Mary’s, the love of my life – or so I’d thought at the time – had dumped me. I’d driven, heart wrenched in two, to my parents’ farm in Wiltshire, where Jamie had been stabled. He’d poked his head out of his box when he heard my car. I’d walked over and stroked him gently on the nose before letting my head fall on to his. Half an hour later, his nose was soaked in my tears and he hadn’t moved an inch. Had he been physically capable of holding me in his arms, he would have done.

Jamie, beautiful Jamie, as fast as the wind and as strong as a tiger. His great, kind heart had finally given up and the last thing I was ever going to be able to do for him was dig a bloody great hole.

I climbed back into the digger, raised its arm and lowered the bucket. It came up half-full of earth. Not bad. I swung the digger round, dumped the earth, swung back and performed the same sequence again. This time, the bucket was full of compact, dark-brown soil. When we first came here, Duncan joked that if his new business failed, he could beco

me a peat farmer. Peat covers our land to a depth of between one and three yards and, even with the excavator, it was making the job heavy work.

I carried on digging.

After an hour, the rain-clouds had fulfilled their promise, the crow had given up and my hole was around six feet deep. I’d lowered the bucket and was scooping forward when I felt it catch on something. I glanced down, trying to see round the arm. It was tricky – there was a lot of mud around by this time. I raised the arm a fraction and looked again. Something down there was getting in the way. I emptied the bucket and lifted the arm high. Then I climbed out of the cabin and walked to the edge of the hole. A large object, wrapped in fabric stained brown by the peat, had been half-pulled out of the ground by the digger. I considered jumping down before realizing that I’d parked very close to the edge and that peat – by this time very wet – was crumbling over the sides of the hole.

Bad idea. I did not want to be trapped in a hole in the ground, in the rain, with a tonne and a half of mini-excavator toppled on top of me. I climbed back into the cab, reversed the digger five yards, got out and returned to the hole for another look.

And I jumped down.

Suddenly the day became quieter and darker. I could no longer feel the wind and even the rain seemed to have slackened – I guessed much of it had been wind-driven. Nor could I hear clearly the crackle of the waves breaking on the nearby bay, or the occasional hum of a car engine. I was in a hole in the ground, cut off from the world, and I didn’t like it much.

The fabric was linen. That smooth-rough texture is unmistakeable. Although it was stained the rich, deep brown of the surrounding soil I could make out the weave. From the frayed edges appearing at intervals I could see that it had been cut into twelve-inch-wide strips and wrapped around the object like an oversized bandage. One end of the bundle was relatively wide, but then it narrowed down immediately before becoming wider again. I’d uncovered about three and a half feet but more remained buried.

Crime scene, said a voice in my head; a voice I didn’t recognize, never having heard it before. Don’t touch anything, call the authorities.

Get real, I replied. You are not calling the police to investigate a bundle of old jumble or the remains of a pet dog.

I was crouched in about three inches of mud that were rapidly becoming four. Raindrops were running off my hair and into my eyes. Glancing up, I saw that the grey cloud overhead had thickened. At this time of year the sun wouldn’t set until at least ten p.m. but I didn’t think we were going to see it again today. I looked back down. If it was a dog, it was a big one.

I tried not to think about Egyptian mummies, but what I’d uncovered so far looked distinctly human in shape and someone had wrapped it very carefully. Would anyone go to that much trouble for a bundle of jumble? Maybe for a well-loved dog. Except it didn’t seem to be dog-shaped. I tried to run my finger in between the bandages. They weren’t shifting and I knew I couldn’t loosen them without a knife. That meant a trip back to the house.

Climbing out of the hole proved to be a lot harder than jumping in and I felt a flash of panic when my third attempt sent me tumbling back down again. The idea that I’d dug my own grave and found it occupied sprang into my head like a punch-line missing a joke. On my fourth attempt I cleared the edge and jogged back down to the house. At the back door I realized my wellington boots were covered with wet, black peat and I knew I wouldn’t be in the mood for washing the kitchen floor later that evening. We have a small shed at the back of our property. I went in, pulled off my boots, replaced them with a pair of old trainers, found a small gardening trowel and returned to the house.

The telephone in the kitchen glared at me. I turned my back on it and took a serrated vegetable knife from the cutlery drawer. Then I walked back to the . . . my mind kept saying grave site.

Hole, I told myself firmly. It’s just a hole.

Back in it I crouched down, staring at my unusual find, for what felt like a long time. I had an odd feeling that I was about to set off along a hitherto untrodden path and that, once I took the first step, my life would change completely and not necessarily for the better. I even considered climbing out and filling in the hole again, digging another grave for Jamie and never telling anyone what I’d seen. I crouched there, thinking, until I was so stiff and cold I had to move. Then I picked up the trowel.

The earth was soft and I didn’t have to dig for long before I’d uncovered another ten inches of the bundle. I took hold of it round the widest part and pulled gently. With a soft slurping noise the last of it came free.

I reached for the end of the bundle I’d uncovered first and tugged at the linen to loosen it. Then I inserted the tip of the knife and, holding tight with my left hand, drew the knife upwards.

I saw a human foot.

I didn’t scream. In fact, I smiled. Because my first feeling as the linen fell away was enormous relief: I must have dug up some sort of tailor’s dummy, because human skin is never the colour of the foot I was looking at. I let out a huge breath and started to laugh.

Then stopped.

Because the skin was the exact same colour as the linen that had covered it and the peat it had lain in. I reached out. Indescribably cold: undoubtedly organic. Moving my fingers gently I could feel the bone structure beneath the skin, a callus on the little toe and a patch of rough skin under the heel. Real after all, but stained a rich, dark brown by the peat.

The foot was a little smaller than my own and the nails had been manicured. The ankle was slender. I’d found a woman. I guessed she would have been young, in her twenties or early thirties.

I looked up at the rest of the linen-wrapped body. At the spot where I knew the chest would be was a large patch, roughly circular in shape and about fourteen inches in diameter, where the linen changed colour, becoming darker, almost black. Either something peculiar in the soil had affected this patch of linen or it had been stained before she’d been buried.

I really didn’t want to see any more; I knew I had to call the authorities, let them deal with it. But somehow, I couldn’t stop myself from taking hold of the darker linen and making another cut. Three inches, four, six. I pulled the cloth apart to see what was beneath.

Even then I didn’t scream. On legs that didn’t feel like my own I stood up and backed away until I came up against the side of the pit. Then I turned and leaped as if for my life. Clambering out, I was surprised by the sight of the dead horse just yards away. I had forgotten Jamie. But the crow had not. He was perched on Jamie’s head, digging furiously. He looked up, guiltily; then, I swear, he smirked at me. A lump of shiny tissue, dripping blood, bulged from his beak: Jamie’s eye.

That was when I screamed.

I sat by Jamie, waiting. It was still raining and I was soaked to the skin but I no longer cared. In one of our sheds I’d found an old green canvas tent and laid it over Jamie’s body, leaving just his head exposed. My poor old horse was not going to be buried today. I stroked his lovely bright coat and twisted show plaits into his mane as I kept silent vigil by my two deceased friends.

When I could no longer bear to look at Jamie, I raised my head and looked out across the inlet of sea water known as Tresta Voe. Voes, or drowned valleys, are a common feature of this part of the world, dozens of them fraying the coastline like fragile silk. It is impossible to describe accurately the twisting, fractured shapes they make, but from the hill above our house I could see land, then the water of the voe as it formed a narrow, sand-rimmed bay, then a narrow strip of hill, then water again. If I were high enough and had good enough vision, I would be able to see it go on, striping alternately, land and sea, land and sea, until my eyes reached the Atlantic and the rock finally gave up the fight.

I was on the Shetland Islands, probably the most remote and least known part of the British Isles. About a hundred miles from the north-eastern tip of Scotland, Shetland is a group of around a hundred islands. Fifteen are inhabited by people; all of them by puffins, kittiw

akes, bonxies and other assorted wildlife.

Socially, economically and historically, the islands are unusual; geographically, they verge on the bizarre. When we first stood together on this spot, Duncan wrapped his arms around me and whispered that, long ago, a terrible battle was fought between massive icebergs and ancient granite rocks. Shetland – a land of sea caves, voes and storm-washed cliffs – was its aftermath. At the time, I liked the story, but now I think he was wrong; I think the battle goes on. In fact, sometimes I think that Shetland and its people have spent centuries fighting the wind and the sea . . . and losing.

It took them twenty minutes. The white car with its distinctive blue stripe and Celtic symbol on the front wing was the first to pull into our yard. Dion is Cuidich, Protect and Serve, said the slogan. The police car was followed by a large, black, four-wheel-drive vehicle and a new, very clean, silver Mercedes sports car. Two uniformed constables got out of the police car, but it was the occupants of the other cars that I watched as the group headed towards me.

The Mercedes driver looked far too tiny to be a policewoman. Her hair was very dark, brushing her shoulders and layered around her face. As she drew closer I saw that she had fine, small features and hazel-green eyes. Her skin was perfect, lightly freckled across her nose and the colour of caffe latte. She wore new, green Hunter boots, a spotless Barbour coat and crimson wool trousers. There were gold knots in her ears and several rings on her right hand.

Beside her the man from the four-wheel-drive looked enormous, at least six two, possibly three, and broad across the shoulders. He too wore a Barbour and green wellingtons but his were scuffed, shiny and looked a dozen years old. His hair was thick and gingery-blond and he had the high-coloured, broken-capillaried complexion of a fair-skinned person who spends a lot of time outdoors. His hands were huge and callused. He looked like a farmer. I stood up when they approached and dropped a piece of canvas over Jamie’s head. You can say what you like, but in my book even horses have a right to privacy.

The Split

The Split Daisy in Chains

Daisy in Chains The Craftsman

The Craftsman A Dark and Twisted Tide

A Dark and Twisted Tide Little Black Lies

Little Black Lies Here Be Dragons: A Short Story

Here Be Dragons: A Short Story Alive

Alive Like This, for Ever

Like This, for Ever Now You See Me

Now You See Me Sacrifice

Sacrifice