- Home

- Sharon Bolton

A Dark and Twisted Tide

A Dark and Twisted Tide Read online

About the Book

Former detective Lacey Flint quit the force for a safer, quieter life. Or that’s what she thought.

Now living alone on her houseboat, she is trying to get over the man she loves, undercover detective Mark Joesbury. But Mark is missing in action and impossible to forget. And danger won’t leave Lacey alone.

When she finds a body floating in the river near her home, wrapped in burial cloths, she can’t resist asking questions. Who is this woman, and why was she hidden in the fast-flowing depths? And who has been delivering unwanted gifts to Lacey?

Someone is watching Lacey Flint closely.

Someone who knows exactly what makes her tick . . .

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Prologue

Saturday, 28 June

Chapter 1

Thursday, 19 June

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Tuesday, 12 February

Chapter 14

Friday, 20 June

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Sunday, 23 March

Chapter 30

Saturday, 21 June

Chapter 31

Sunday, 22 June

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Monday, 23 June

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Friday, 4 April

Chapter 39

Tuesday, 24 June

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Thursday, 26 June

Chapter 43

17 May

Chapter 44

Friday, 27 June

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Saturday, 28 June

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Sunday, 29 June

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Monday, 30 June

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Tuesday, 1 July

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Wednesday, 2 July

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

Chapter 88

Chapter 89

Chapter 90

Chapter 91

Chapter 92

Chapter 93

Chapter 94

Chapter 95

Chapter 96

Thursday, 3 July

Chapter 97

Friday, 18 July

Chapter 98

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Sharon Bolton

Copyright

A DARK AND TWISTED TIDE

SHARON BOLTON

In memory of Margaret Yorke, who was my neighbour, my mentor and my friend.

And according to the success with which you put this and that together, you get a woman and a fish apart, or a Mermaid in combination. And Mr Inspector could turn out nothing better than a Mermaid, which no Judge and Jury would believe in.

Charles Dickens, Our Mutual Friend

Prologue

I AM LACEY Flint, she tells herself, as dawn breaks and she lifts first one arm then the other, kicking hard with legs that are longer and more powerful than usual, thanks to a stout pair of fins. My name is Lacey, she repeats, because this mantra of identity has become as much a part of her daily ritual as swimming at first light. Lacey, which is soft and pretty, and Flint, sharp and hard as nails. Sometimes Lacey is amused by the inherent contrast of her name. Other times, she admits it suits her perfectly.

I am Constable Lacey Flint of the Metropolitan Police’s Marine Unit, Lacey announces silently to her reflection in the mirror, as she dresses in her pristine uniform and sets off for her new head quarters at Wapping police station, taking comfort in the knowledge that, for the first time in many months, a police officer feels like who she was meant to be.

I am Lacey Flint, she says to herself most nights, as she battens down the hatches of her houseboat and crawls into the small double bed in the forward cabin, listening to water slapping against the hull and the scrabble of creatures setting out for the night. I live on the river, work on the river and swim in the river.

I am Lacey and I am loved, she thinks, as a tall man with turquoise eyes steps once again to the front of her thoughts.

‘I am Lacey Flint,’ she sometimes murmurs aloud as she drifts away to the world of what-ifs, could-bes and still-mights that other people call sleep; and she wonders whether there might ever come a day when she forgets that it is all a massive lie.

SATURDAY, 28 JUNE

1

The Killer

THE PUMPING STATION sits near the embankment wall of the River Thames in London, close to the border of Rotherhithe and Deptford, like a woman at a dance who has long since given up hoping for a partner. The small, square building has mostly been forgotten by the people who walk, cycle or drive past it each day, if indeed they ever noticed it in the first place. It has always been there, like the roads, the high river wall, the riverside path. Not a striking building, in any sense, and nothing ever happens in connection with it. No deliveries come to the wide wooden doors on one side and certainly nothing comes out. The windows are all sealed with wooden planks and heavy steel nails. Occasionally, someone lingering on the riverside path might notice that the brickwork is a perfect example of Flemish diagonal bond and that the pattern surrounding the flat roof is beautiful, in an understated way.

Few do. The roof is above normal sight lines and the nearest road isn’t on a bus route. River traffic, of course, is far below. So no one ever appreciates that the pale grey of the building is relieved by bricks of white in a repeating criss-cross pattern, and by uniform pieces of stone set on the diagonal. The Victorians decorated everything, and they didn’t neglect this insignificant building, even if few of them would have mentioned its original purpose in polite company. The pumping station was built to pump human sewage from the lower-lying lands of Rotherhithe and discharge it into the Thames. It once played an important role in keeping the surround

ing streets fresh, but bigger, more efficient stations were brought into play, and there came a day when it was no longer needed.

If passers-by were curious enough to find a way inside, they’d see that, Tardis-like, the interior is so much bigger than its external framework suggests, because at least half of the pumping station is underground. Two storeys up, the boarded-up windows and the large double door are all high in the walls. To reach them, it is necessary to climb an iron staircase and step along an ornate gallery that runs round the entire circumference of the chamber.

All the engineering equipment has long since been taken away, but the decoration remains. Stone columns rise to the roof, their once-crimson paint faded to a dull red. Tudor roses still entwine at the tops of the pillars, even though they no longer gleam snow-white. Mould creeps up the sides of the smooth brickwork, but can’t hide the fine quality of the bricks. Anyone privileged to see inside the pumping station would consider it a minor architectural gem, somewhere to be preserved and celebrated.

It can’t happen. For years now, it has been in private hands, and those hands have no interest in development or change. Those hands are unconcerned that a piece of riverside real estate this close to the city is probably worth millions. All those hands care about is that the old pumping station serves a purpose particular to them.

It also happens to be the ideal place to shroud a dead body.

In the centre of the space are three iron plinths, each roughly the size of a modest dining table. The dead woman lies on the one closest to the outlet pipe and the killer is panting with the exertion of getting her there. Water streams off them both. The dead woman’s hair is black and very long. It clings to her face like the weed on an upturned boat hull at low tide.

Above, the moon is little more than a curled blond eyelash in the sky, but there are streetlamps along the embankment and some light reaches inside. Together with the glow from several oil lanterns set in the arched recesses of the walls, it is enough.

When the hair is gently lifted, the pale, perfect face beneath is revealed. The killer sighs. It is always so much easier when their faces haven’t been damaged. The wound around the neck is ugly, but the face is untouched. The eyes are closed and that is good, too. Eyes so quickly lose their lustre.

Here it comes again, that heavy sadness. Regret – there is no other word for it really. They are so lovely, the girls, with their flowing hair and long limbs. Why lure them away with promises of rescue and safety? Why live for the moment when the hope in their eyes turns to terror?

Enough. The body has to be undressed, washed and shrouded. It can be left here for the rest of the night and taken out to the river tomorrow. Close to hand are the hemmed sheets, the nylon twine and the weights.

The woman’s clothes are soon removed; the cotton tunic and trousers are cut away easily, the cheap underwear is the work of seconds.

Oh, but she’s so beautiful. Slender. Long, slim legs; small, high breasts. Pale, perfect skin. The killer’s strong fingers run the length of the firm, plump thigh, trace the outline of the small round kneecap and go on down the perfectly formed shin, over the spreading curve of the calf. Perfect feet. The high, graceful arch of the instep, the tiny pink toes, the perfect oval of the toenails. In death, she is the absolute picture of unattainable femininity.

A rasping sound. Then a cold, strong hand clutching the killer’s arm.

The woman is moving. Not dead. Her eyes are open. Not dead. She’s coughing, wheezing, her hands scrabbling around on the iron block, trying to get up. How did this happen? The killer almost faints in shock. Eyes that have turned black with horror are staring. More river water comes coughing out of those pale, bitten lips.

Lips that should not have anything more to say.

The killer reaches out, but isn’t quick enough. The woman has scrambled back and fallen off the plinth. ‘Ay, ay,’ she cries, the sound of a terrified animal. The killer, too, is terrified. Is it all over, then?

The woman is on her feet. Bewildered, disorientated, but not so much that she has forgotten what happened to her. She starts backing away, staring round, looking for a way out. When her eyes meet those of her killer they open wider in dismay. Words come out of her mouth, which may or may not be the words the killer hears.

‘What are you?’

And it’s enough to bring back the rage. Not ‘Who are you?’ Not ‘Why are you doing this?’ Both of which would be perfectly reasonable questions in the circumstances. But ‘What are you?’

The woman is running now, looking for a window – which she won’t find on this floor – or a door, which won’t help her.

She’s spotted the upper floor, is heading for the staircase. There is no way out up there – the windows are all boarded, the heavy door can’t be opened – but there are skylights that she might be able to break, attracting the attention of people outside.

The killer surges forward, crashing painfully into the iron frame of the steps, catching hold of the woman’s ankle, biting hard on the fleshy part of the calf. A howl of pain. Another hard pull. A squawk, then she comes tumbling down.

The killer has her now, but the woman is naked and slippery with water and sweat. She isn’t easy to hold and she’s fighting like an eel. The biting and scratching and the continual wriggling are exhausting. The killer’s grip loosens. The woman is up. Reach out, grab. She’s fallen, slapped down hard on the stone floor, hit her head. Dazed, she’s easier to manage. Heave. The sound of flesh scraping along stone. Arms flailing, claw-like hands trying to grab hold of something – anything – but they’ve reached the smooth, metal pipe that in the old days took the water out of here. Lift her in. Climb after her. Push her along. The pipe is short, not much more than a metre in length.

There is water below, feet away, and gravity is helping now. Lean, pull and – yes – they both hit the surface.

And the world becomes calm again. Silent. Soft and easy.

Easy now. Let go. Let her sink. Let her panic. Wait for her to rise up, to take her last desperate breath, then make your move. Up and out of the water in one massive surge, and down again with your hands around her throat. Then down, down into the depths. Down until she stops struggling.

Two of them clasped together. A tight embrace. A good way to die.

THURSDAY, 19 JUNE

(nine days earlier)

2

Lacey

A SINGLE DROP of rain falling on the village of Kemble in the Cotswolds is destined to become part of the longest river in England and one of the most famous in the world. On its 216-mile journey to the North Sea, that one drop will hook up with the hundreds of millions of others that wash daily past London Bridge.

Sometimes, as she swam amongst them, Lacey Flint thought about those millions of drops and her entire body shivered with excitement. Other times, the notion of the unstoppable force of water all around made her want to scream in terror. She never did, though. Catch a mouthful of the Thames this close to the estuary and there was every chance it could kill you.

So she kept her head up and her mouth largely shut. When she opened it to snatch in air, because muscles swimming at speed through cold water need oxygen, she relied upon a prior rinsing with Dettol to kill the bugs on contact. For nearly two months now, since she’d bought the vintage sailing yacht that was her new home, she’d been wild-swimming in the Thames as often as tide and conditions allowed, and she was healthier than she’d ever been.

At 05.22 hours on a June morning, as close to the solstice as made little difference, the river was already busy and, even staying close to the south bank, she had to take care. River traffic didn’t always stick to the middle of the channel and no boat pilot was ever looking out for swimmers.

The tide was as high as it was going to get. There was a moment at high tide, especially in summer, when the river seemed to pause and become still. For just a few minutes – ten, maybe fifteen – the Thames became as easy to glide through as a pool and Lacey could forget that

she was human, dependent on a wetsuit and fins and antiseptic rinse to survive in this strange, aquatic environment and become, instead, part of the river.

A sleek arrowhead of a gull skimmed the water ahead, before disappearing below the surface. Lacey pictured it beneath her, beak open wide, scooping up whatever fish it had spotted from above.

She carried on, towards the jagged black pilings of one of the derelict offshore landing stages that ran along this stretch of the south bank. Built when London was one of the busiest commercial ports in the world to allow larger vessels to moor up and offload their cargo, they had fallen into disrepair decades ago.

Not for the first time, Lacey found herself missing Ray. She missed seeing his skinny arms ahead of her, missed the shower of bright water when he occasionally kicked too high, but he’d picked up a summer cold a few days earlier and his wife, Eileen, had put her foot down. He was staying out of the river until he was well again.

Less than thirty metres to the landing stage. Her senses on full alert, as they always were in the river, something caught her eye. There was movement in the water, over by the bank. Not flotsam – it had been holding its position. There were otters on the Thames, but she’d not heard of any this far down. Other people swam in the river, according to Ray, but higher up where the water was cleaner and the flow more gentle. As far as he knew, he and now Lacey were the only wild-swimmers this close to the estuary.

Slightly unnerved, Lacey struck out faster, suddenly wanting to get past the landing stages, turn into Deptford Creek and be on the home stretch.

Almost there. Ray usually swam through the pilings, a little ritual of his own, but Lacey never got too close. There was something about the blackened, mollusc-encrusted wood that she didn’t like.

Another swimmer, after all, directly ahead. Lacey felt the moment of elation that comes from shared pleasure. Especially the guilty sort. She got ready to smile as the woman came closer, maybe tread water for a few seconds and chat.

Except – that wasn’t swimming. That was more like bobbing. The arm that, a second ago, had seemed to be waving now moved randomly. And the arm wasn’t just thin – it was skeletal. For a second the woman was upright. Then she lay flat before disappearing altogether. Another second later she was back. Maybe not even a woman; the long hair Lacey had seen in the dazzling, reflected light now looked like weed. And the clothes, trailing like a veil around the corpse, had added to the feminine effect. The closer she got, the more sexless the thing appeared.

The Split

The Split Daisy in Chains

Daisy in Chains The Craftsman

The Craftsman A Dark and Twisted Tide

A Dark and Twisted Tide Little Black Lies

Little Black Lies Here Be Dragons: A Short Story

Here Be Dragons: A Short Story Alive

Alive Like This, for Ever

Like This, for Ever Now You See Me

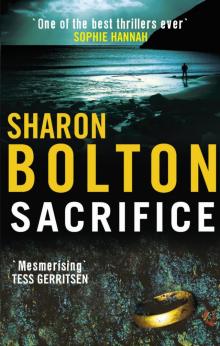

Now You See Me Sacrifice

Sacrifice