- Home

- Sharon Bolton

Alive

Alive Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

1

Susan

A dark moon is rising.

A perfect black circle, barely visible in the night sky, the dark moon casts its void over the wind-scorched moor, over the soaring mass of a great limestone hill and over the town that cowers in its shadow. The dark moon is the absence of moon before the slender silver crescent of the new moon appears again and people can breathe a little easier.

The month is March and the night is clear and cold, black as pitch. The full moon in March is known as the Worm Moon, welcome despite its ominous name, marking as it does the end of winter and the emergence of earthworms from the thawing ground. Dark moons have never been named, although they are sometimes called the dead moons. The dark moons reign over nights when people stoke up their fires, draw their curtains tighter and try to think happy thoughts. In the town of Sabden at the foot of Pendle Hill in Lancashire, they usually fail.

In Sabden’s soot-blackened terraced houses, the sleepers’ dreams darken when the moon leaves the sky. Infants wake up cold, mothers tremble with elusive fears for their children, and old folks slip a little closer to death. Even the town’s witches are afraid, casting salt circles round their homes for protection and burning sage leaves to ward off evil spirits. Only the Craftsman welcomes the dark moon.

When the town is at its most still, when the only creature astir is the dog that stalks the railway-arch tramps in the refusal to believe he is an unloved stray, the Craftsman roams, ever watchful. He walks the silent streets, keeping always to the shadows. He avoids soft ground where he might leave footprints, but a window without drawn curtains is irresistible to him. He does not linger, but his footsteps might slow a little as he passes down the length of Springfield Street, because it is here, at number 17, that Susan lives.

Monday, 17 March 1969

Susan Duxbury was unique among her class of fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds because she liked Mondays. Loved them, in fact. Susan got up early on Mondays to get to the bathroom before the rest of the family and, in cold water, because it was never hot first thing in the morning, washed her fringe and the front two inches of her long dark brown hair. Susan had greasy hair that needed washing every day, but bath times were once a week in the Duxbury household and Susan’s night was Friday. She didn’t have time to wash her entire head of hair, but the couple of inches closest to her face made a difference. When that front strip of hair was clean, she washed her face, underarms, feet and between her legs, and squeezed a fresh spot that had appeared on her chin overnight. Satisfied at last, she crept back along the thin upstairs carpet to the room she shared with her older and younger sisters.

Apart from a pale light creeping in from the streetlamps outside, the room was in darkness, but Susan could see Stella wriggling and stretching beneath her blankets as she dressed in bed. Most mornings in winter, Susan did that too, but not on Mondays. Mondays were too important. Bracing herself against the cold, she pulled off her nightdress and tugged on her school uniform. She definitely had lost weight since … well, since it had happened – her skirt was inches looser than it had been. When she heard her mother go downstairs to light the kitchen fire, she ran along the corridor to her parents’ room. Dad was never an alert presence in the house at breakfast time – if he wasn’t at work or asleep, it meant he was in prison – and so Susan was free to dab foundation on the worst of her spots and perfume on her wrists. Make-up wasn’t allowed at school, but foundation didn’t count. Foundation was invisible.

By the time the family of six were gathered round the kitchen table, the eight-o’clock news on the radio was predicting severe storms around the Orkney Islands in Scotland, with several vessels already believed to be in danger. As the newsreader moved on to a story about the Kray twins beginning their life sentences for murder, Susan was polishing off her cornflakes and blowing on her tea to cool it. Susan was always first to leave the house. On Mondays.

As she ran through St Giles’s Churchyard – a shortcut, though a bit spooky on these dark mornings – she was surprised to see the town sexton hard at work, but the long winter had killed off a lot of the old folk. Susan giggled at the thought of a queue of corpses lining up for their funerals, because she was young, and death was something that happened to other people. She took a detour when she was in sight of the school building, so that she could skirt round the car park. Sometimes they arrived at the same time and she got to say, ‘Morning, sir,’ before anyone else in the whole school. It was her punctuality that had made him notice her, he’d told her – that and her long, sweet-smelling dark hair. And her gorgeous, gorgeous bum. No one had ever said nice things to Susan before. Not her family, and certainly not the boys at school, who called her ‘lardy arse’ and ‘dozy cow’. What did they know?

She slowed her pace, slipping with practised ease into her film-star walk, taking small, deliberate steps and letting her hips swing.

Too late. The red Hillman Hunter, the nicest car in the teachers’ car park, was there already, parked next to the empty milk-bottle crates. One day, he’d promised her, she’d get to ride in that car. The pang of disappointment at not seeing him left her soon. It was Monday, after all. Last period was geography. Her favourite.

* * *

David Milner, who taught geography at Sabden Secondary Modern, got home shortly after four o’clock and made himself a sandwich of Mother’s Pride bread and seedless raspberry jam. As he stuffed the food into his mouth, he wondered if he’d made the bed that morning and decided he didn’t care. He should probably draw the curtains, though, if only so he didn’t have to look at her face. With a bit of luck, she wouldn’t want to kiss him again, because just the thought of that acne-ridden mush reeking bad breath was enough to make him gag. He reminded himself that he chose the ugly ones for a reason. The ugly ones were grateful. The ugly ones believed you were in love, that there was a future and that the secrecy would only be for a short time. The ugly ones were less likely to be believed if they ever decided to tell. Duxbury might be the ugliest he’d had in years, but her father had been in prison more times than anyone could remember, and her mother was barely articulate. As long as he didn’t get her pregnant, he could keep this going for months. And with the curtains drawn, taken from behind, at least he wouldn’t have to worry about her face. His erection was rubbing against his trousers. ‘Down, boy,’ he muttered, giving it an encouraging rub as he glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece. The bitch was actually late.

* * *

Susan left school at four-fifteen, a quarter of an hour after lessons had finished for the day, but she hadn’t wanted to get trapped into walking home with any of the other girls. Besides, David was always so good about giving her the excuse she needed, asking her to tidy the classroom or, as he’d done that day, sending her with a note to one of the other teachers. David. Maybe today she’d ask him if she could call him David. It felt a bit weird, to be honest, calling him Mr Milner when he was …

She hurried down

Union Street and past the police station. On the corner of Market Street, she saw the new policewoman, the first female constable in Lancashire, according to the local paper. Her name was Flora, or Fiona, or Florence. That was it – the girls at school had been talking about how weird it would be to be named after a character in The Magic Roundabout and how none of them could decide whether the policewoman was attractive or not. Most of the girls agreed that they hated ginger hair and freckles, and wouldn’t be able to stand wearing a thick black police officer’s uniform. Susan hadn’t argued, but could they not see that Florence’s skin was pale but perfect, that her hair shone a rich red gold and her eyes were wide and blue as cornflowers? Even in her ugly flat shoes she walked with a dancer’s grace, and her voice was clear and sweet, high-pitched and clipped in a way that made Susan think of TV stars or real-life princesses.

Florence was talking to a tall, dark-haired man whom Susan thought was also a police officer, though he didn’t wear uniform. He was good-looking too, and he was staring at Florence as they spoke. A wave of doubt rushed through Susan as she realised that David had never looked at her the way the dark-haired police officer was looking at Florence.

Susan kept her head down as she hurried past. There was no reason why they’d stop her, no reason at all – lots of kids came home from school this way – but sometimes she felt as though her secret were bursting out of her and someone else, a police officer maybe, would be sure to see it. Technically, she was too young to have sex, but as Mr Milner – David – explained to her, that was just in their culture. In other countries around the world, girls got married when they were fourteen, even younger.

‘I can’t marry you till you’re sixteen,’ he’d said, ‘though we should probably leave it until you’ve left school completely. Bright girl like you, you could go to college.’

Susan loved that he knew she was bright. None of the other teachers could spot that. She glanced in a shop window to see back along the street. The two police officers were still engrossed in their conversation. They hadn’t even seen her. Not far now. She’d go in the back way, as she always did, through the ginnel, ducking beneath any washing that had been hung out, until she reached his yard door. He’d be waiting in the kitchen. He always took her straight up to his bedroom. Four more streets to cross, three more, then— Oh God, no. Some kids she knew from school, actually in her class, were coming towards her. They’d ask her where she was going, and she could never think up excuses on the spot. She had a quiet, steady intelligence, that’s what David had told her; she needed time to be clever. On an impulse, she turned up the street she was crossing. It ran parallel to David’s so she could approach his house from the top of the ginnel instead.

As Susan hurried up the street, out of breath because the road was steep, a van drew up alongside. The driver, a man she knew, wound down the window. Susan slowed her steps a little.

‘You all right, love?’ The driver looked her up and down. ‘You look a bit hot and bothered.’

It was Mr Glassbrook, the dad of one of her school friends. He was the town undertaker, but he never seemed creepy. He actually looked a bit like Elvis Presley, with his slicked-back black hair and his smart, colourful jackets.

‘I’m all right, thanks,’ Susan said. ‘I’m just going to my friend’s.’

She had a moment of dread that he’d ask her which friend. She had no idea who lived at the top of this street. He didn’t, though. Instead, he said, ‘Hop in, love. I’ll give you a lift to t’top.’

* * *

Susan’s family didn’t get concerned until it was nearly six o’clock. She was never home from school before five-thirty on Monday because she helped tidy up the geography class and then went to a friend’s house to do homework. By half past six, Susan’s mother was starting to wonder if she should have asked which friend.

The police began looking for Susan shortly before eight o’clock. They phoned the neighbouring force to request assistance from the dog unit and diverted all available officers to the house-to-house search. They looked all night.

They were wasting their time. Susan was with the Craftsman. Sixteen hours after she was abducted, she was dead.

When he realised that the living, kicking, screaming girl had become a lifeless corpse, the Craftsman got up from where he had been lying on the hard, frost-glazed earth. He threw back his head and tossed a soundless howl to the absent moon. After a while, when the threat of rage had subsided, he went home to check on the date of the next dark moon.

2

Stephen

The April full moon comes early in 1969, glowing over the landscape on the second day of the month, when frosted windows still greet the townsfolk of Sabden at daybreak, and when the coal fog hangs low over rooftops as night falls.

The full moon in April is known as the pink moon, after the blooming of the ground phlox, which covers the land in a blanket of small pink flowers. Phlox has never bloomed wild in Lancashire, and when the witches gather high above the town, the moors are still the dull browns and dried yellows of winter.

In April, the Craftsman knows that the long nights are drawing to an end. The whole winter has gone by and he has yet to achieve his purpose. He knows his work will be so much harder in the summer, when the evenings are light and the people of the town linger outdoors. In summer, his ability to move around unseen will be lessened.

For the first two weeks of April, as the dark moon draws closer, the Craftsman grows anxious. He has had a second child in his sights for some time now. He knows the child’s movements and routines, his friends and his habits, better than do the boy’s own parents. But so much, so very much depends on chance.

Wednesday, 16 April 1969

Stephen Shorrock was playing football on a patch of spare land three streets from where he lived when his mate Jimmy ran up, red-faced and panting. ‘Oi, lads!’ he called. ‘That dwarf freak is in St Andrew’s. He’s digging.’

The boys looked towards Stephen. Knowing they would take their lead from him, he thought about it. His side was winning, but …

The ‘dwarf freak’ was the sexton, the man who held a grim fascination for the town’s children. It wasn’t just that he was shorter than most of them, with an odd, inharmonious body and a great protruding brow, more that he buried the dead and must have seen more corpses than they’d watched episodes of Blue Peter. They liked to watch him work. They liked to stop him working. They liked to bait him from afar, the way their ancestors might have poked sticks into a tethered bear, because when the sexton became riled, his temper bore no relation at all to his diminutive size. And he was dangerous. The games wouldn’t be half as much fun if he weren’t.

‘Let’s do it,’ Stephen said.

The six lads, all fourteen and fifteen years old, from the same school in Sabden, left the spare land, scooping up school sweaters that had served as goalposts and calling schoolboy insults to each other to disguise their nerves. Roger brought his football, clutched tight to his chest like a shield. They ran, panting, up the hill and round the corner. At the top of Gillibrand Street, they paused, because Danny Earnshaw, son of the chairman of the town council, was riding a new bike. It was a Raleigh Chopper, a revolutionary design that had been launched just two weeks earlier. The boys had seen coverage on the nightly news, had never imagined they’d see one in Sabden quite so soon. They stared, but Danny Earnshaw was with his gang, and you didn’t mess with that lot if you were wise. The boys carried on running, under the fencing, across the railway line and down into the street behind St Andrew’s Church. Stephen gestured that they should take cover behind the church wall while he scoped out the scene. The boys dropped to the ground, panting, and Stephen raised his head.

Dwane Ogilvy, a man of around twenty-seven, although to the children he appeared as old as Methuselah, was standing in the grave, in shirt-sleeves, his hairline damp with sweat. He was working with a spade, bending and digging before tossing the earth into a long, rectangular box lying alongside.

Round the edge of the hole, Dwane had placed a wooden template, a guide to make sure the grave was perfect. A rectangular piece of plywood lay a little distance away and on it Dwane had placed the turf he’d removed from the ground, arranging the pieces like a jigsaw puzzle so that they could be replaced neatly on the finished grave. On the ground were several more spades, some heavy-duty knives and a pick. Dwane might be only a digger of graves, but he did the job well. For the first time, Stephen found himself feeling a grudging respect for the dwarf. For a second, he was tempted to change his mind, but then he saw the faces of his mates and knew he’d never hear the end of it.

‘Jimmy, Craig, go round that side.’ Stephen pointed to the wall opposite. ‘Rog, Duffy, that way.’ He pointed to the corner. ‘Sugs stays with me.’

The four boys hurried away and took their places round the wall. Stephen waited until Dwane was looking down before directing an urgent finger at Rog and Duffy. They were ready. They popped up like meerkats and hurled stones at Dwane’s back. Rog was the better shot. His stone landed in the grave beside the sexton. Duffy’s fell short by several feet.

Dwane stopped what he was doing and spun round. Rog and Duffy had already ducked low. Stephen watched as the little man frowned and waited for a long minute before turning back to his job. Exactly as Stephen had expected, though, Dwane shifted his position around so that he was facing the wall where Rog and Duffy were hiding. Stephen waited for five more spades of earth to land in the box before he directed his finger at Jimmy and Craig. They appeared, threw their stones and ducked. These two were better shots. One stone landed in the grave; the other caught Dwane on the arm.

‘Who’s there?’ The dwarf whirled round and his normally sallow colour had turned pink. ‘Pack it in or I’ll have you.’

The boys didn’t answer. Of course they didn’t – this was far too much fun – and after a minute or two, Dwane resumed his work. He was on his guard now, though, glancing up every few seconds. That was fine. That was how it was supposed to work. His heart beating fast, Stephen gave the signal, a different one this time, to Rog and Duffy. They stood and threw. Neither stone hit its mark, but Dwane heard them fall. He looked up, saw the two boys and leaped out of the grave. Rog and Duffy set off running. They were the two fastest of the group and had been chosen specially for this job, because Dwane might have short legs but he could run fast. He raced across the uneven grass towards the two boys and vaulted over the churchyard wall to give chase.

The Split

The Split Daisy in Chains

Daisy in Chains The Craftsman

The Craftsman A Dark and Twisted Tide

A Dark and Twisted Tide Little Black Lies

Little Black Lies Here Be Dragons: A Short Story

Here Be Dragons: A Short Story Alive

Alive Like This, for Ever

Like This, for Ever Now You See Me

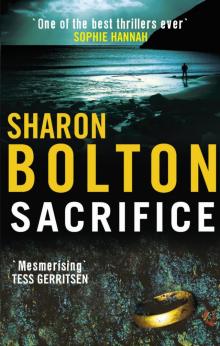

Now You See Me Sacrifice

Sacrifice