- Home

- Sharon Bolton

Like This, for Ever

Like This, for Ever Read online

About the Book

Bright red. Like rose petals. Or rubies. Little red droplets.

Barney knows the killer will strike again soon. The victim will be another boy, just like him. He will drain the body of blood, and leave it on a Thames beach.

There will be no clues for detectives Dana Tulloch and Mark Joesbury to find.

There will be no warning about who will be next.

There will be no good reason for young policewoman Lacey Flint to become involved…

And no chance that she can stay away.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Part Two

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Part Three

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by S. J. Bolton

Copyright

For Hal, who peeps out at me through every child in this book; and for his mates, who gamely played along.

‘Do you not know that tonight, when the clock strikes midnight, all the evil things in the world will have full sway?’

Dracula, Bram Stoker

Prologue

‘THEY SAY IT’S like slicing through warm butter, when you cut into young flesh.’

For a second, the counsellor was still. ‘And is it?’ she asked.

‘No, that’s complete rubbish.’

‘So, what is it like?’

‘Well, granted, the first part’s easy. The parting of the skin, that first rush of blood. The knife practically does it for you, as long as it’s sharp enough. But after that first cut you have to work pretty hard.’

‘I imagine so.’

‘The body’s fighting you, for one thing. From the moment you cut, it’s trying to heal itself. The blood starts to clot, the artery or vein or whatever it is you’ve opened is trying to close and the skin is producing that icky, yellowy stuff that eventually becomes a scab. It’s really not easy to go beyond that first cut.’

‘It seems to be largely about the first cut for you, would that be fair to say?’

The patient nodded in agreement. ‘Definitely. By the time the knife touches skin, the noise in my head is close to unbearable – I feel like my skull’s about to blow apart. But then there’s that first drop of blood, and the next, and then it’s just streaming out.’

The patient was leaning forward eagerly now, as though the act of confession, once begun, was unstoppable.

‘I’ll tell you what it’s like – it’s like that first heavy snowfall in winter, when suddenly everything’s beautiful and the world falls silent. Well, blood does exactly the same thing as snow. Suddenly, the pain means nothing, all that noise in my head has gone away. Somehow, with that first cut, I’ve gone to another place entirely. A place where, finally, there’s peace.’

Gently, almost apologetically, the counsellor closed her notebook. ‘We’re going to have to stop now,’ she said. ‘But thank you, Lacey. I think, at last, we’re getting somewhere.’

PART ONE

1

Thursday 14 February

THE SADNESS WAS inside him always. A dull pressure against the front of his chest, a bitter taste in his mouth, a hovering sigh, just beyond his next breath. Most of the time he could pretend it wasn’t there, he’d grown so used to it over the years, but the second he felt his focus shift from the immediate on to the important there it was again, like the creature lurking beneath the bed. Deep, unchanging sadness.

Barney waited for Big Ben to strike the fourth note of eight o’clock before pushing the letter into the postbox. The sadness faded a little, he’d done everything right. This time could work.

Important task over with, he felt himself relax and start to notice things again. Someone had tied a poster to the nearest lamppost. The photograph of the missing boys, ten-year-old twins Jason and Joshua Barlow, took up most of the A4 sheet of card. Both had dark-blond hair and blue eyes. One twin was smiling in the picture, his new adult teeth uncomfortably large in his mouth; the other was the serious one of the pair. Both were described as 1.40m tall and slim for their age. They looked exactly like thousands of other boys living in South London. Just like the two, possibly three, who had gone missing before them.

Someone was watching. Barney always knew when that was happening. He’d get a feeling – nothing physical, never the prickle between the shoulder blades or the cold burn of ice on the back of his neck, just an overwhelming sense of someone else’s presence. Someone whose attention was fixed on him. He’d feel it, look up, and there would be his dad, with that odd, thoughtful smile on his face, as though he were looking at something wonderful and intriguing, not just his eleven-year-old son. Or his teacher, Mrs Green, with the raised eyebrows that said he’d been off on one of his daydreams again.

Barney turned and through the window of the newsagent’s saw Mr Kapur tapping his watch. Barney kicked off and in a steady glide reached the shop door.

‘Late to be out, Barney,’ said Mr Kapur, as he’d taken to doing over the last few weeks. Barney opened the upright cool cabinet and reached for a Coke.

‘Fifty pence minus ten per cent staff discount,’ said Mr Kapur, as he always did. ‘Forty-five pence, please, Barney.’

Barney handed over his money and tucked the can in his pocket. ‘You going straight home now?’ asked Mr Kapur, his last words drowned by the bell as Barney pulled open the door.

Barney smiled at the elderly man. ‘See you in the morning, Mr Kapur,’ he said, as he pulled the zip of his coat a little higher.

There was a fierce wind coming off the river as Barney picked up speed on his roller blades and travelled east along pavements still gleaming with rain. The wind brought the smell of diesel and damp with it and Barney had a sense, as he always did, of the river reaching out to him. He imagined it escaping its confining banks, finding underground passageways, drains, sewers,

and seeping its way up into the city. He could never be near the river without thinking of black water flowing beneath the street, an invasion so subtle, so cautious, that no one except him would notice until it was too late. He’d confided his fear once to his dad, who’d laughed. ‘I think you’re overlooking some basic laws of physics, Barney,’ he’d said. ‘Water doesn’t flow uphill.’

Barney hadn’t mentioned it again, but he knew perfectly well that sometimes water did flow uphill. He’d seen pictures of London submerged by floodwater, read accounts of how high spring tides had coincided with strong downstream flows and the river’s cage had been unable to contain it. Given a chance of freedom, the water had leaped from its banks and roared its way through London like an angry mob.

It could happen. There had been snow in the Chiltern Hills. It would be melting, the thaw water making its way down through the smaller tributaries, reaching the Thames, which would be getting fuller and faster as it neared the capital city. Barney picked up speed, wondering how fast he’d have to skate to outrun floodwater.

When Barney reached the community centre the building looked deserted. No lights, so even the caretaker had gone, which meant it had to be after nine o’clock. With a familiar feeling of dread, he looked at his watch. He’d said goodnight to Mr Kapur just after eight o’clock. The newsagent’s was a ten-minute skate away. It had happened again. Time, inexplicably, had been lost.

A voice from beyond the wall, the sound of wheels on iron. The others were waiting for him in the yard, but suddenly Barney wanted nothing so much as to go straight home. Sooner or later – sooner if he was smart, and he was, wasn’t he? Everyone agreed that Barney was clever, a bit weird sometimes, but bright – he would have to tell someone about these missing hours of his.

A low laugh. He thought he heard his own name. Barney pushed the worry to the back of his mind and carried on round the corner. The community centre had once been a small Victorian factory. Surrounding it were various outbuildings and a tarmac yard, all encased within a high brick wall topped with iron railings. Inside the main building were a library, a crèche for pre-school children, an after-school club and a youth club. Barney and his friends hung out at the youth club several nights a week, but it was after the centre closed that the place became their own.

In the alleyway at the back, Barney reached for the loose railing and got ready to pull himself up.

In this city, someone is always watching.

What was that doing in his head right now? Why, now, should he remember the talk they’d had at school from the local community police officer? She’d been talking about how every Londoner could expect to be caught on CCTV several hundred times a day. But Barney knew for a fact there were no cameras in the alley and the surrounding streets, or overlooking the centre. It was one of the reasons his gang hung out here.

He ran his eyes along the row of houses opposite, looking for the light in the window, the undrawn curtains, the gleam of eyes that would confirm what he knew – that someone was watching. Nothing.

Except they were, and with that certain knowledge came a knocking in his chest as if his heart had suddenly moved up a gear. OK, here he was, in the city where five boys his age had disappeared in as many weeks, on his own in the exact part of London where they had all lived, and someone he couldn’t see was watching him.

Barney scrambled through the gap in the railings, skates still on his feet, knowing it was a stupid thing to do, but adrenaline and determination just about kept him the right way up. He rolled forward. Right, which side of the wall were the eyes? Street side or factory side? Cut off from him by nine feet of solid Victorian brickwork and iron railing, or trapped inside with him? The contents of his stomach turned to something like cold lead as he realized he might just have made the biggest mistake of what was going to be a very short life.

He could no longer hear the others. For now it was just an eleven-year-old boy, a very high wall, and an unseen pair of eyes.

Directly ahead, between Barney and the main yard, was the Indian village: five small wigwams in which the younger kids played during the day. Even on a normal night, Barney couldn’t look at them without imagining someone – maybe a toddler left behind by an absent-minded parent – peeping out at him from the blackness. He never liked being near the Indian village at night, even without … he checked each dark interior in turn before moving on. Nothing.

Nothing that he could see.

Just beyond the wigwams was one of the murals that had been painted on the inside of the perimeter walls. Scarlet-clad pirates, their sights on distant treasure, clung to the rails of a galleon on a troubled sea. In the daytime, the murals were faded, the paint peeling in places. During the hours of darkness, the tangerine glow of the streetlights brought them to life. The green forests around the gates had depth and a sense of secrets lurking behind giant trees, the starry night sky beyond the skateboard ramp seemed endless. Without the sun’s harsh scrutiny, even the pirates seemed to be watching him.

At last, from the corner of the factory building, he could peer round into the quadrangle that was the main part of the yard. The relief almost hurt. At the top of the skateboard ramp sat four still figures. His best mate, Harvey, then Sam and Hatty, two kids in Harvey’s class, and finally Lloyd, who was a couple of years older. Against the streetlamp light they seemed entirely clad in black. Barney caught a gleam of eyes as one of them looked round. He could also see the tiny red glow of a couple of cigarettes. At the sight of his gang, doing what they always did, looking completely relaxed, Barney started to calm down too. For once, his instincts had cried wolf.

A sudden noise, loud and shrill, blared directly above his head. Then someone jumped down, grabbing him around the throat.

2

THE CHILDREN WERE beautiful. They lay curled on their sides, spooned together. The fingers of the boy in front looked as though they were about to twitch and stretch, as sunlight and his internal body clock told him it was time to wake. Even in the flat light of the tent, he didn’t look dead. Neither did his brother, snuggled up behind him, one arm slung carelessly across his sibling’s chest.

‘Boss!’

Dana started. Her gloved hand was reaching out towards the closest boy’s forehead, where a damp lock of hair had fallen forward. She’d been about to brush it out of his eyes, the way a mother would. She still wanted to – to smooth it back over his head, pull covers up over their shoulders and keep the night air from their skin, bend and brush her lips over the soft cheeks.

Stupid. She didn’t have children, had never known maternal feelings in her life. That they should kick in now, that a couple of dead, ten-year-old boys should be the ones to awaken them.

‘Boss,’ repeated the other living occupant of the tent, a heavy-set man with thinning red hair and an indistinct chin-line. ‘Tide’s coming in fast. We need to get them out of here.’

Detective Inspector Dana Tulloch, of Lewisham’s Major Investigation Team, let Detective Sergeant Neil Anderson help her to her feet. They moved out of the police tent and into the smell of salt, rotting vegetation and petrol fumes that was the night air by the tidal Thames. The waiting crowd on Tower Bridge wriggled in anticipation. Light flashed as someone took their photograph.

As she and Anderson stepped away, others took their place, moving quickly. In a little over thirty minutes, the area would be under several feet of water. The two detectives walked up the beach towards the embankment wall.

‘Right under Tower Bridge,’ said Dana, looking up at the massive steel structure. ‘One of the most iconic landmarks in London, not to mention one of the busiest spots. What is he thinking of ?’

‘He’s a cheeky bastard,’ agreed Anderson.

Dana sighed. ‘Who was first on the scene?’ she asked.

‘Pete,’ Anderson replied, looking around. ‘He was here a minute ago.’

Dana watched as more SOCOs made their way gingerly down Horselydown Old Stairs, the slimy concrete steps that offered t

he only access point to this stretch of the riverbank.

‘He’s killing them faster, Neil,’ she said. ‘We’ve never found them this quickly before.’

‘I know, Boss. Here’s Pete.’

Detective Constable Pete Stenning, thirty-one years old, tall and good looking with dark curly hair, was jogging lightly down the steps to join them.

‘What can you tell us, Pete?’ she asked, when he was close enough.

‘They were spotted at 20.15 by the local florist,’ said Stenning. ‘I was with him just now. He’s had a busy day, what with it being Valentine’s Day, and he’s got a big wedding on tomorrow so he and a couple of assistants were working late. He needed a fag and smoking in the street is frowned upon so he tends to wander down the lane and up Horselydown steps. Finds it soothing to watch the river, he says, and there’s shelter if it’s pissing it down. His words, not mine.’

‘And he spotted them?’

‘There was just enough light from the Brewhouse behind and the bridge in front, he says, although he wasn’t entirely sure what he was looking at till he went down to the beach. And before you ask, he saw nothing else. The two women in the shop confirm his story.’

‘Any thoughts on how they were brought here?’ asked Anderson.

‘Could have come by water,’ said Stenning, ‘but personally, I doubt it. This is a bloody treacherous place to bring a boat in at anything other than very high water.’ He gestured over towards the river’s edge. ‘There’s the remains of a Victorian embankment just under the water there,’ he went on. ‘If your boat hits that at any speed, chances are you’re going down.’

‘Road, then?’ said Dana.

‘More likely,’ said Stenning. ‘One thing you should see,’ he went on. ‘Just a bit further under the bridge.’

Dana and Anderson followed Stenning into the shadows beneath Tower Bridge, trying to ignore the craning necks and intense stares just a few feet above them. Then all attention switched from the police officers to the small black bags being carried out of the police tent. The boys were being taken away. A few outraged cries broke out, as though the police on the beach were responsible for what had happened to the children.

The Split

The Split Daisy in Chains

Daisy in Chains The Craftsman

The Craftsman A Dark and Twisted Tide

A Dark and Twisted Tide Little Black Lies

Little Black Lies Here Be Dragons: A Short Story

Here Be Dragons: A Short Story Alive

Alive Like This, for Ever

Like This, for Ever Now You See Me

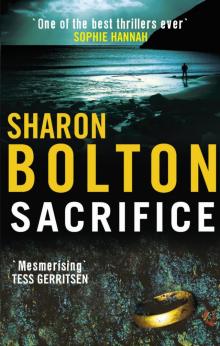

Now You See Me Sacrifice

Sacrifice