- Home

- Sharon Bolton

Now You See Me

Now You See Me Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Prologue

Part One - Polly

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Part Two - Annie

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

Part Three - Elizabeth

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

Part Four - Catharine

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

Part Five - Mary

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

Also by S. J. Bolton

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright Page

For Andrew, who reads my books first; and for Hal, who can’t wait to get started.

Prologue

Eleven years ago

LEAVES, MUD AND GRASS DEADEN SOUND. EVEN SCREAMS. The girl knows this. Any sound she might make can’t possibly travel the quarter-mile to the car headlights and streetlamps, to the illuminated windows of tall buildings that she can see beyond the wall. The nearby city isn’t going to help her and screaming will just burn up energy she can’t spare.

She’s alone. A moment ago she wasn’t.

‘Cathy,’ she says. ‘Cathy, this isn’t funny.’

Difficult to imagine anything less funny. So why is someone giggling? Then another sound. A grinding, scraping noise.

She could run. The bridge isn’t far. She might make it.

If she runs, she leaves Cathy behind.

A breeze stirs the leaves of the tree she’s standing beside and she finds she can’t stop shaking. She dressed, a few hours ago, for a hot pub and a heated bus-ride home, not this open space at midnight. Knowing that any second now she may have to run, she lifts first one foot and then the other and takes off her shoes.

‘I’ve had enough now,’ she says, in a voice that doesn’t sound like her own. She steps forward, away from the tree, a little closer to the great slab of rock lying ahead of her on the grass. ‘Cathy,’ she says, ‘where are you?’

Only the scraping answers back.

The stones look taller at night. Not just bigger, but blacker and older. Yet the circle they make seems to have shrunk. She has a sense of those just out of her line of sight slipping closer, playing grandmother’s footsteps; that if she spins round now, there they’ll be, close enough to touch.

Unthinkable not to turn with an idea like that in her head; not to whimper when a dark shape plainly is moving closer. One of the tall stones has split in two like a splinter of rock breaking away from a cliff. The splinter stands free and steps forward.

She runs then, but not for long. Another black shape is blocking her path, cutting off her route to the bridge. She turns. Another. And another. Dark figures make their way towards her. Impossible to run. Useless to scream. All she can do is turn on the spot, like a rat caught in a trap. They take hold of her and drag her towards the great, flat rock and one thing, at least, becomes clear.

The sound she can hear is that of a blade being sharpened against stone.

Part One

Polly

‘The brutality of the murder is beyond conception and beyond description.’

Star, 31 August 1888

1

Friday 31 August

A DEAD WOMAN WAS LEANING AGAINST MY CAR.

Somehow managing to stand upright, arms outstretched, fingers grasping the rim of the passenger door, a dead woman was spewing blood over the car’s paintwork, each spatter overlaying the last as the pattern began to resemble a spider’s web.

A second later she turned and her eyes met mine. Dead eyes. A savage wound across her throat gaped open; her abdomen was a mass of scarlet. She reached out; I couldn’t move. She was clutching me, strong for a dead woman.

I know, I know, she was on her feet, still moving, but it was impossible to look into those eyes and think of her as anything other than dead. Technically, the body might be clinging on, the weakening heart still beating, she had a little control over her muscles. Technicalities, all of them. Those eyes knew the game was up.

Suddenly I was hot. Before the sun went down, it had been a warm evening, the sort when London’s buildings and pavements cling to the heat of the day, hitting you with a wave of hot air when you venture outside. This was something new, though, this pumping, sticky warmth. This heat had nothing to do with the weather.

I hadn’t seen the knife. But I could feel the handle of it now, pressing against me. She was holding me so tightly, was pushing the blade further into her own body.

No, don’t do that.

I tried to hold her away, just enough to take the pressure off the knife. She coughed, except the cough came from the wound on her throat, not her mouth. Something splashed over my face and then the world turned around us.

We’d fallen. She sank to the ground and I went with her, hitting the tarmac hard and jarring my shoulder. Now she was lying flat on the pavement, staring up at the sky, and I was kneeling over her. Her chest was still moving – just.

There’s still time, I told myself, knowing there wasn’t. I needed help. None to be had. The small car park was deserted. Tall buildings of six- and eight-storey blocks of flats surrounded us and, for a second, I caught a movement on one of the balconies. Then nothing. The twilight was deepening by the second.

She’d been attacked moments ago. Whoever had done it would be close.

I was reaching for my radio, patting pockets, not finding it, and all the while watching the woman’s eyes. My bag had fallen a few feet away. I fumbled inside and found my mobile, summoning police and ambulance to the car park outside Victoria House on the Brendon Estate in Kennington. When I ended the call, I realized she’d taken hold of my hand.

A dead woman was holding my hand, and it was almost beyond me to look into those eyes and see them trying to focus on mine. I had to talk to her, keep her conscious. I couldn’t listen to the voice in my head telling me it was over.

‘It’s OK,’ I was saying. ‘It’s OK.’

The situation was clearly a very long way from OK.

‘Help’s coming,’ I said, knowing she was beyond help. ‘Everything’s goin

g to be fine.’

We lie to dying people, I realized that evening, just as the first sirens sounded in the distance.

‘Can you hear them? People are coming. Just hold on.’ Both her hand and mine were sticky with blood. The metal strap of her watch pressed into me. ‘Come on, stay with me.’ Sirens getting louder. ‘Can you hear them? They’re almost here.’

Footsteps running. I looked up to see flashing blue lights reflected in several windows. A patrol car had pulled up next to my Golf and a uniformed constable was jogging towards us, speaking into his radio. He reached us and crouched down.

‘Hold on now,’ I said. ‘People are here, we’ll take care of you.’

The constable had a hand on my shoulder. ‘Take it easy,’ he was saying, just as I’d done seconds earlier, only he was saying it to me. ‘There’s an ambulance on its way. Just take it easy.’

The officer was in his mid forties, heavy set, with thinning grey hair. I thought perhaps I’d seen him before.

‘Can you tell me where you’re hurt?’ he asked.

I turned back to the dead woman. Really dead now.

‘Love, can you talk to me? Can you tell me your name? Tell me where you’re injured?’

No doubt about it. Pale-blue eyes fixed. Body motionless. I wondered if she’d heard anything I’d said to her. She had the most beautiful hair, I noticed then, the palest shade of ash blonde. It spread out around her head like a fan. Her earrings were reflecting light from the streetlamps and there was something about the way they sparkled through strands of her hair that struck me as familiar. I released her hand and began pushing myself up from the pavement. Gently, someone kept me where I was.

‘I don’t think you should move, love. Wait till the ambulance gets here.’

I hadn’t the heart to argue, so I just kept staring at the dead woman. Blood had spattered across the lower part of her face. Her throat and chest were awash with it. It was pooling beneath her on the pavement, finding tiny nicks in the paving stones to travel along. In the middle of her chest, I could just make out the fabric of her shirt. Lower down her body, it was impossible. The wound on her throat wasn’t the worst of her injuries, not by any means. I remembered hearing once that the average female body contained around five litres of blood. I’d just never considered quite what it would look like when it was all spilling out.

2

‘I’M OK, I’M NOT HURT. IT’S NOT MY BLOOD.’

I wanted to stand up; they wouldn’t let me move.

Three paramedics were huddled around the blonde woman. They seemed to be holding pressure pads against the wound on her abdomen. I heard mention of a tracheotomy. Then something about a peripheral pulse.

Shall we call it? I think so, she’s gone.

They were turning to me now. I got to my feet. The woman’s blood was sticky against my skin, already drying in the warm air. I felt myself sway and saw movement. The blocks of flats surrounding the square had long balconies running the length of every floor. A few minutes ago they’d been deserted. Now they were packed with people. From the back pocket of my jeans I pulled out my warrant card and held it up to the nearest officer.

‘DC Lacey Flint,’ I said.

He read it and looked into my eyes for confirmation. ‘Thought you looked familiar,’ he said. ‘Based at Southwark, are you?’

I nodded.

‘CID,’ he said to the hovering paramedics who, having realized there was nothing they could do for the blonde woman, had turned their attention on me. One of them moved forward. I stepped back.

‘You shouldn’t touch me,’ I said. ‘I’m not hurt.’ I looked down at my bloodstained clothes, feeling dozens of eyes staring at me. ‘I’m evidence.’

I wasn’t allowed to slink off quietly to the anonymity of the nearest police station. DC Stenning, the first detective on the scene, had received a call from the DI in charge. She was on her way and didn’t want me going anywhere until she’d had chance to speak to me.

Pete Stenning had been a colleague of mine at Southwark before he’d joined the area’s Major Investigation Team, or MIT, based at Lewisham. He wasn’t much older than me, maybe around thirty, and was one of those lucky types blessed with almost universal popularity. Men liked him because he worked hard, but not so hard anyone around felt threatened, he liked down-to-earth, working-class sports like football but could hold down a conversation about golf or cricket, he didn’t talk over-much but whatever he said was sensible. Women liked him because he was tall and slim, with curly dark hair and a cheeky grin.

He nodded in my direction, but was too busy trying to keep the public back to come over. By this time, screens has been erected around the blonde woman’s body. Deprived of the more exciting sight, everyone wanted to look at me. News had spread. People had sent text messages to friends, who’d hot-footed it over to join in the fun. I sat in the back of a patrol car, avoiding prying eyes and trying to do my job.

The first sixty minutes after a major incident are the most important, when evidence is fresh and the trail to the perpetrator still hot. There are strict protocols we have to follow. I didn’t work on a murder team, my day-to-day job involved tracing owners of stolen property and was far less exciting, but I knew I had to remember as much as possible. I was good at detail, a fact I wasn’t always grateful for when the dull jobs invariably came my way, but I should be glad of it now.

‘Got you a cup of tea, love.’The PC who’d appointed himself my minder was back. ‘You might want to drink it quick,’ he added, handing it over. ‘The DI’s arrived.’

I followed his glance and saw that a silver Mercedes sports car had pulled up not far from my own car. Two people got out. The man was tall and even at a distance I could see he was no stranger to the gym. He was wearing jeans and a grey polo shirt. Tanned arms. Sunglasses.

The woman I recognized immediately from photographs. Slim as a model, with shiny, dark hair cut into a chin-length bob, she was wearing the sort of jeans women pay over a hundred pounds for. She was the newest senior recruit to the twenty-seven major investigation teams based around London and her arrival had been covered officially, in internal circulars, and unofficially on the various police blog sites. She was young for the role of DI, not much more than mid thirties, but she’d just worked a high-profile case in Scotland. She was also rumoured to know more about HOLMES 2, the major incident computer system, than practically any other serving UK police officer. Of course, it didn’t hurt, one or two of the less supportive blogs had remarked, that she was female and not entirely white.

I watched her and the man pull on pale-blue Tyvek suits and shoe covers. She tucked her hair into the hood. Then they went behind the screens, the man standing aside at the last moment to allow her to go first.

By this time, white-suited figures were making their way around the site like phantoms. The scene-of-crime officers had arrived. They would establish an inner cordon around the body and an outer one around the crime scene. From now on, everyone entering the cordons would be signed in and out, the exact time of their arrival and departure being recorded. I’d learned all this at the crime academy, only a few months ago, but it was the first time I’d seen it in practice.

A gazebo-like structure was being erected over the spot where the corpse still lay. Screens has already been put up to create walls and within seconds the investigators had a large, enclosed area in which to work. Police tape was set up around my car. Lights were being unloaded from the van just as the DI and her companion emerged. They spoke together for a few seconds then the man turned and walked off, striding over the striped tape that marked the edge of the cordon. The DI came my way.

‘I’ll leave you to it,’ said my minder. I handed him my cup and he moved away. The new DI was standing in front of me. Even in the Tyvek suit she looked elegant. Her skin was a rich, dark cream and her eyes green. I remembered reading that her mother had been Indian.

‘DC Flint?’ she asked, in a soft Scottish accent. I nodded.

3

‘OK,’ SAID DI TULLOCH. ‘GO SLOWLY AND KEEP TALKING.’ I set off, my feet rustling on the pavement. Tulloch had taken one look at me and insisted that a Tyvek suit and slippers be brought. I’d be getting cold, she said, in spite of the warm evening, and I’d attract much less attention if the bloodstains were covered up. I was also wearing a pair of latex gloves to preserve any evidence on my hands.

‘I’d been on the third floor,’ I said. ‘Flat 37. I came down that flight of stairs and turned right.’

‘What were you doing there?’

‘Talking to a witness.’ I stopped and corrected myself. ‘A potential witness,’ I went on. ‘I’ve been coming over on Friday evenings for a few weeks now. It’s the one time I can be pretty certain not to see her mother. I’m trying to persuade her to testify in a case and her mother isn’t keen.’

‘Did you succeed?’ asked Tulloch.

I shook my head. ‘No,’ I admitted.

We reached the end of the walkway and could see the square again. Uniform were trying to persuade people to go home and not having much luck.

‘Guess there isn’t much on TV tonight,’ muttered Tulloch. ‘Which case?’

‘Gang rape,’ I replied, knowing I could probably expect trouble. I didn’t work on crime involving sexual assault and earlier that evening I’d been moonlighting. A few years ago the Met set up a number of bespoke teams known as the Sapphire Units to deal with all such offences. It was the sort of work I’d joined the police service to do and I was waiting for a vacancy to come up. In the meantime, I kept up to speed on what was going on. I couldn’t help myself.

‘Was the passage empty when you came out of the stairwell?’ Tulloch asked.

‘I think so,’ I said, although the truth was I wasn’t sure. I’d been annoyed at the response I’d got from Rona, my potential witness; I’d been thinking about my next move, if I even had one. I hadn’t been paying much attention to what was going on around me.

‘When you came out into the square, what did you see? How many people?’

The Split

The Split Daisy in Chains

Daisy in Chains The Craftsman

The Craftsman A Dark and Twisted Tide

A Dark and Twisted Tide Little Black Lies

Little Black Lies Here Be Dragons: A Short Story

Here Be Dragons: A Short Story Alive

Alive Like This, for Ever

Like This, for Ever Now You See Me

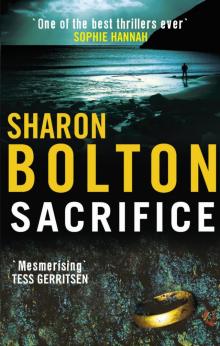

Now You See Me Sacrifice

Sacrifice