- Home

- Sharon Bolton

Like This, for Ever Page 3

Like This, for Ever Read online

Page 3

Only when she’d reached the first step that wasn’t encrusted with river-weed did Dana feel her heartbeat begin to slow down. She turned back, one last time. By this time, it was impossible to tell where the beach ended and the water began. She could still hear it though, the soft, whispering sound it made as it crept towards her.

5

‘WILL YOU BE working on the murders when you go back?’ Barney asked Lacey, as they turned into the road where they both lived. Lacey looked down at the boy, only a few years away from becoming a man, and yet whose face was so fresh, whose skin so clear and whose thought processes so blindingly obvious. He was thinking that his stock with his gang of mates would soar if he had an inside track on a murder investigation. Especially one involving kids. People were invariably most interested in murders when they were potential victims themselves.

She was almost sorry to disappoint him. ‘No, I don’t work on murders,’ she said. ‘My job isn’t anything like that exciting.’

She could see him watching, waiting for her to tell him what her job was, hoping it would be something like Drugs, Vice or the Flying Squad. But how could she explain to a boy she barely knew that she didn’t think she would ever work as a police officer again?

‘You and your mates are good,’ she said. ‘I’ve watched you a couple of times now. If the light catches you the right way, especially against the mural with stars on it, you look like you’re flying.’

‘My mates are scared of you,’ he said.

The words seemed to take them both by surprise. Barney’s lips were clenched tight and he had an oh shit look in his eyes.

‘Are you?’ she asked him.

‘No,’ he said after a second. ‘But then, I knew you before.’

Before. This child, whom she’d spoken to less than a dozen times, could remember what she’d been like before. Jesus, even she couldn’t remember that any more.

Barney had stopped moving. ‘He’s here again.’ His voice had lowered, giving a hint of the man’s that was to come in a few years, and something about its tone put her on full alert. She stopped, too.

‘Who’s here?’ she asked. Two middle-aged women were walking away from them further up the street. There was no one at Barney’s front door.

‘The man that watches you.’

Lacey wondered at the complexity of the human heart that could feel fear, misery and joy, all at the same time. All with the same root cause. ‘What man?’ she asked, although she knew perfectly well.

‘The one who sits in his car outside your house,’ the boy replied. ‘Who knocks on your door a lot.’

‘Where is he?’ she asked him. ‘Don’t point or look, just tell me.’

The kid was bright, he did exactly that. ‘He’s in a green car on the left-hand side of the road about six – no, seven – cars away from us.’

So strong, the temptation to look for the car, to make sure he was right. ‘How on earth did you spot that?’

Barney shrugged, looked uncomfortable. ‘I just see things,’ he said.

‘What do you mean, you just see things? I wouldn’t even have known there was a green car that far down the street, but you not only see the car, you see a man sitting inside it, in the dark.’

He sighed. ‘The colours of the cars are reflected in the water on the road,’ he said. ‘There’s a silver one, a black one, red, two more silver, white van, then his green one.’

He couldn’t see the line of parked cars any more. She was blocking his view. If he was right, it was extraordinary. Incredible powers of observation and recall.

‘The streetlights are shining through the cars,’ he went on. ‘The light comes straight through most of them, but in the green one there’s something that gets in its way. A dark, solid shape, which can only be a largeish head and shoulders. A man, sitting inside a green car. It’s obvious.’

‘I think we need to get you working for the Met,’ said Lacey.

His face softened. ‘I’ve always been good at finding things,’ he said. ‘When I was a kid, I used to find four-leaf clovers in the grass. My mum collected them in a box for me. I’ve still got them. If you lose anything – you know, jewellery and stuff – just give me a ring. I’ll probably find it.’

‘I have very little jewellery,’ said Lacey. ‘But I could use a four-leaf clover, next time you find one.’

‘I don’t really see them any more,’ he said, taking her seriously. ‘I grew out of that. I see other things now. Lost things.’

They crossed the road and stopped at Barney’s front door. Neither of them had looked back at the green car but Barney’s eyes couldn’t settle. ‘Are you worried about him?’ he asked her.

She shook her head. ‘No, we sort of work together. Actually, he’s more of a friend.’

A look altogether too mature for an eleven-year-old appeared on his face. A friend? Who hung around outside her flat, banging on the door because she wouldn’t answer his telephone calls?

‘He’s worried about me,’ she went on. ‘I’ve been ill, you see. I just don’t want to talk to anyone right now.’

The too-grown-up look disappeared, to be replaced by one that was all kid. ‘Except me,’ he said, smiling at her.

It was surprisingly easy to smile back. ‘Yeah, except you.’

Lacey was about to wish Barney goodnight when she thought to glance up at the house. All the windows were in darkness. There wasn’t even a light in the hallway.

‘Is your dad home?’ she asked him. It was after half nine. Kids of his age, mature or not, shouldn’t be on their own that late. If someone reported it to her at the station, she’d be duty bound to check it out.

‘Probably,’ said Barney. ‘He may have nipped out. Or he could be in his study. It’s at the back of the house, so you wouldn’t see a light.’

He couldn’t make eye contact any more. He was lying. He knew perfectly well his father wasn’t in the house.

‘Do you want me to come and sit with you till he gets back?’ she asked, knowing it would keep the occupant of the green car at bay a little longer. Maybe he’d even give up and go home.

Barney shook his head. ‘I’ll be fine,’ he said. ‘He’s probably in. I’m just going to go to bed.’

‘Do you have a phone?’

He pulled it from his pocket and held it out. ‘Have you cut yourself ?’ she asked him, holding back from taking it.

A look of panic, as sharp and unexpected as a slap, crossed his face. He looked down quickly, as though noticing for the first time that his fingers were smeared with something that looked a lot like blood.

‘Yuck!’ He wiped his hands backwards and forwards on his jacket, a look of extreme distaste on his face. Then he shuddered. ‘No,’ he said. ‘Just something I must have touched.’

Lacey smiled, took the phone and tapped both her mobile and landline numbers into his contacts list. ‘Just in case you need me,’ she told him. He nodded, unlocked his front door and turned to say goodnight.

‘Wash your hands before you eat anything,’ she called. He was looking over her shoulder, at the line of parked cars in the road.

‘I expect he’ll be knocking soon,’ he said, before disappearing inside.

6

THE HOUSE WAS a mess as usual. Barney looked round at the supper remains all over the granite worktop, the skewed window blind, his dad’s sweater abandoned on a stool, two drawers not quite shut, one cupboard door wide open. Somehow, the rule that said grown-ups were supposed to tidy up after their kids had skipped the Roberts’ house.

He turned on the hot tap and ran it over his hands. He hadn’t cut himself, he was pretty certain he hadn’t, but that icky stuff on his hands had looked, for a second, like blood. He soaped and rinsed them several times before getting to work on the kitchen. Tidiness had been important to his mum; it was one of the few things he could remember about her.

At the kitchen sink, Barney raised the blind to straighten it. Light in the garden next door told him that Lacey

was in her conservatory at the back of her small flat.

Lacey could help him find his mum.

The dishes done, Barney let the water drain away. He couldn’t understand why he hadn’t thought of it before. The police tracked down missing people all the time. But if he told anyone what he was doing, he’d jinx it and it would fail. Somehow he knew that. He couldn’t tell anyone. And what if she told his dad?

When everything had been put away and all the surfaces were clean again, Barney went up two flights of stairs to the top floor. On the way, he switched off the divert that sent all incoming calls to his mobile. He wasn’t supposed to go out when his dad wasn’t home.

On the second floor of their house were Barney’s bedroom, bathroom and his den. On one wall of his den was a giant poster of the solar system, on the other a large artist’s impression of a black hole. He wasn’t particularly interested in astronomy, the two posters had just been the biggest he could find on Amazon. He pulled out the eight map pins that held them to the wall and rolled them up. Underneath were his investigations. The first was about the boys who’d been killed. Their photographs, taken from news sites, ran along the top. Beneath them, he’d fastened a map of the river with tiny coloured stickers marking the spots where the bodies had been found. Barney didn’t think there was much chance of his dad finding his investigations, he hardly ever came into his den, but he had a plan just in case. He would say they were for a school project about the work of the Metropolitan Police.

He ran his finger along the course of the river, starting way downstream in Deptford where the first body had been found. The killer was working his way up-river, getting closer. Barney’s finger hovered near Tower Bridge.

On the wall opposite was another large map, this time of all the London boroughs. Right now, he was doing Haringey. The envelopes he’d posted earlier each contained a classified ad to go into the Haringey Independent and the Haringey Advertiser. BARNEY RUBBLE was the bold heading at the top, because that had been his mum’s name for him when he was little. Barney Rubble, after the Flintstones character. That was the attention-grabber. The message below he changed often, because he still hadn’t decided which would work the best. Sometimes it just said: MISSING YOU. Other times it was chatty, quite informal: WOULD LOVE TO CATCH UP SOME TIME. Once, he’d even tried: DIES A LITTLE EVERY DAY WITHOUT YOU, but he’d regretted that the moment he’d posted it. It just wasn’t the sort of thing you said in a newspaper, even if it was anonymous. Even if it was true.

The ads always ended with an email address, the one he’d set up in secret, which only he knew about. The one he checked every morning of his life because this could be the day his mum finally got in touch.

Next month he’d move on to Islington. By the time he was thirteen he’d have done the whole of Greater London and it would be time to move on to the Home Counties.

It didn’t matter really, if his dad found this map. He would never guess what it was all about. It was just important, somehow, to keep it to himself.

Replacing both astronomy posters, Barney crossed the room to his desktop computer. In his in-box were a couple of emails from friends at school, one from his PE teacher, Mr Green, about a fixture that weekend, and a long list of notifications telling him people had replied to a comment stream he’d contributed to on Facebook. Strictly, Barney wasn’t old enough to be on Facebook, but most of his class had their own pages. They just lied about their year of birth. He looked at the time; he had a few minutes before he was supposed to go to bed.

On Facebook he went straight to the Missing Boys page that had been set up a few weeks earlier, when Ryan Jackson had become the second South London boy to vanish. 5,673 people were now following the site and, as always, there was a huge number of posts, ranging from the sensible to the downright weird.

One guy thought the boys were being used for unorthodox medical experiments in a secret research facility somewhere along the riverbank.

Some comments appeared to be from genuine friends of the boys, others from strangers offering best wishes for their safety. Not all the comments were good-natured, and there were the usual people expressing outrage that a social media site should encourage this sort of ‘wallowing’ in others’ misery.

Finally, Barney neared the bottom of the thread. God, some people were weird. And this guy, Peter Sweep, was probably the weirdest of the lot. No profile picture, for one thing, just a photograph of some blood-red roses. No personal information either, although that wasn’t so unusual for kids on Facebook. He had nearly five hundred friends, but they all seemed to be others who’d ‘liked’ the Missing Boys page. It looked like a page set up purely to comment on the murders. Barney sat looking at Peter’s latest post, the last in the thread.

Very exciting – two dead already. Now maybe two more!

The thread updated itself and Barney read with interest. It was Peter Sweep again.

Update on the Barlow Twins case. Lewisham police have recovered two bodies from the bank of the Thames this evening. Announcement expected shortly. RIP Jason and Joshua, now to be known as the Heavenly Twins.

Peter Sweep was one of the most regular contributors to the Missing Boys site. His posts always started out factual, almost official sounding, and in the early days more than one person had speculated that Peter was connected to the police investigation in some way. Certainly everything he posted turned out to be right. But then he always added a sick little message at the end, which made it seem highly unlikely he was a police officer.

In the few seconds since Peter had posted, a flood of comments had followed. Barney spotted Lloyd joining in with the conversation and, a few seconds later, Harvey. As usual, people were eager for more information, including how Peter had come by his scoop. As usual, he didn’t respond.

A thought struck Barney from nowhere. If he went missing, if his face was on television every night, in newspapers, on posters and flysheets that were handed out at train and bus stations, would his mum see them? Would that be enough to bring her back? He could spend years steadily making his way through all the regional papers, spending every penny he had, and not get close. But if he went missing, in one fell swoop he’d get national coverage. That would have to work, wouldn’t it? She’d have to come back then.

Barney stood up, suddenly tired of the Facebook site and its contributors faking sympathy for emotions they’d never feel. How many of them had any idea what it felt like to love one person more than anything in the whole world, and have no idea where she was? He was getting it again, the feeling that made him want to break something, throw something fragile against the wall, or hurl a chair at the window. Pour ink over the carpet. Deep breaths. In for four, out for four. Where was the box? Barney’s breathing was getting away from him, he couldn’t control it. In for four, out for four. He left his den and went into his bedroom. The simple, square rosewood box was in the exact centre of his bedside table. Inside it were small, wizened, green pieces of foliage sitting on tissue paper. Seven of them in total, his four-leaf-clover collection.

He’d been just two when he’d found his first one. He and his mum had been in the park, with a group of other mums and toddlers. He couldn’t remember the occasion himself, but he remembered his mum telling him about it later. ‘I was talking to one of the other mums and you squeaked for my attention like you always did. Then you held your hand out to me and said, “Mummy four. Not free. Four.” And there it was in your chubby little hand, the first four-leaf clover I’d ever seen in my life.’

Over the next couple of years, he’d become obsessed with the idea of finding four-leaf clovers. He looked at the ground and saw the patterns among the grass and the clover. The ones with four leaves jumped out at him. ‘How do you do it?’ his mother would ask. At almost four, the age he’d been when his mother had left, he’d found his last one. He couldn’t remember whether she’d seen it or not.

Barney’s breathing had settled. He closed the box and put it back down beside the bed. Tea

rs filled his eyes. He could find four-leaf clovers. He could find any number of things that were lost. Why couldn’t he find his mum?

7

THE DOOR OF the terraced house was opened by the Family Liaison Officer. She took one look at Dana’s face and stepped back quickly so that the two of them could get inside, away from the reporters who’d been positioned outside the Barlow family home for the past two days. Inside the house, Dana could hear voices on a television programme and music upstairs.

‘Where are they?’ she asked.

‘Lounge,’ replied the FLO. She knew. They always did.

Dana let the FLO lead the way along the hall and through a door on the right. The room was long and narrow, running almost the full length of the house. The family was sitting on easy chairs, pretending to watch television. The mother, father and one of the mother’s sisters, who seemed to have worked out a rota between them, and the twins’ fourteen-year-old brother, Jonathan. Their sixteen-year-old sister was in her room, if the music drifting down the stairs was anything to judge by.

Seeing Dana, Mr Barlow rose and turned off the television set. He stood by its side, waiting. His wife seemed to have frozen in place on the sofa.

‘I have news,’ said Dana, her eyes flicking from the mother to the father. ‘Would you like me to speak to you alone?’ Her eyes wandered to their son. He caught her meaning instantly and moved across the sofa to sit next to his mum. He took hold of her hand, looking frightened and much younger than fourteen.

‘Go on,’ said the dad. He knew, too. They all did. ‘Get on with it.’

‘I’m very sorry, but we found the bodies of two young boys this evening. We believe they’re Jason and Joshua. I’m so very sorry.’

‘Two?’ he said. ‘Both of them?’

The Split

The Split Daisy in Chains

Daisy in Chains The Craftsman

The Craftsman A Dark and Twisted Tide

A Dark and Twisted Tide Little Black Lies

Little Black Lies Here Be Dragons: A Short Story

Here Be Dragons: A Short Story Alive

Alive Like This, for Ever

Like This, for Ever Now You See Me

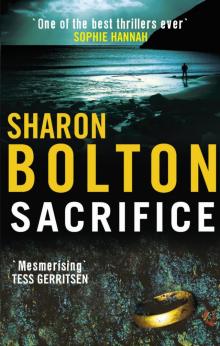

Now You See Me Sacrifice

Sacrifice